Features

Herbicides

Seed & Chemical

Managing weeds with herbicide layering

Research trials in the U.S., and more recently at the University of Saskatchewan, are proving what’s old is new again. In this case, the use of “old” herbicides such as Avadex, Fortress and Edge are making a comeback of sorts in a weed management system that’s been dubbed “herbicide layering.”

May 18, 2017 By Janet Kanters

Studies at the U of S found that using three different modes of action provided weed control and yield benefits in canola. Research trials in the U.S. and more recently at the University of Saskatchewan are proving what’s old is new again.

Studies at the U of S found that using three different modes of action provided weed control and yield benefits in canola. Research trials in the U.S. and more recently at the University of Saskatchewan are proving what’s old is new again.According to Clark Brenzil, who coined the term, herbicide layering is simply utilizing two to three herbicides in sequence to tackle tough-to-control weeds and to stave off weed resistance.

Indeed, herbicide tank mixtures and/or a program that utilizes a residual product in a sequential program are now the recommended practice for delayed herbicide resistance.

“It’s a good management tool for controlling some of those weeds that may not necessarily be that responsive to one herbicide,” Brenzil notes. “Wild oats and cleavers are two great examples of this.”

But even simply switching one herbicide out for another, ie. rotating herbicides, while perhaps delaying the onset of herbicide resistance, still results in selection pressure. Today, many in the industry are starting to stress the importance of using multiple modes of action and tank mixing.

“The extension message is to use multiple modes of action together in weed control programs,” says Mike Grenier, Canadian development manager with Gowan. “But it’s not only using tank mixes – it’s using products in sequence, for instance to look at the soil residual herbicides as part of this management program.”

The idea is simple: apply different modes of action within a season – layering – and rotate chemistries through the crop rotation. As it turns out, Avadex, Edge and Fortress herbicides fit very well into this strategy.

“In our scenario, you would have Group 8, Avadex or Fortress, being soil applied either in the fall or in the early spring followed with a post-emergent program during the growing season,” Grenier notes. “So in this case of Group 1 or Group 2 product use, Avadex is the pre-emergent layer providing resistance management against wild oats.”

In trials, Gowan maintains that Avadex and Fortress can provide about 90 per cent control of wild oat, while Edge (Group 3) provides 70 to 80 per cent suppression. “Then you have a post-emergent program working on a much lower level of [weed] population, so lower selection pressure. So now we have the control level approaching close to 100 per cent.”

Studies find an added bonus

Led by Christian Willenborg, weed scientists at the University of Saskatchewan (U of S) have been conducting research to determine if herbicide layering proves beneficial. “We have some good information in peas and some really good information in canola,” says Eric Johnson, U of S research assistant. “Graduate student Ian Epp’s research in canola showed some benefits, even with Roundup Ready canola, to be using clomazone pre-emergent to improve cleavers control.”

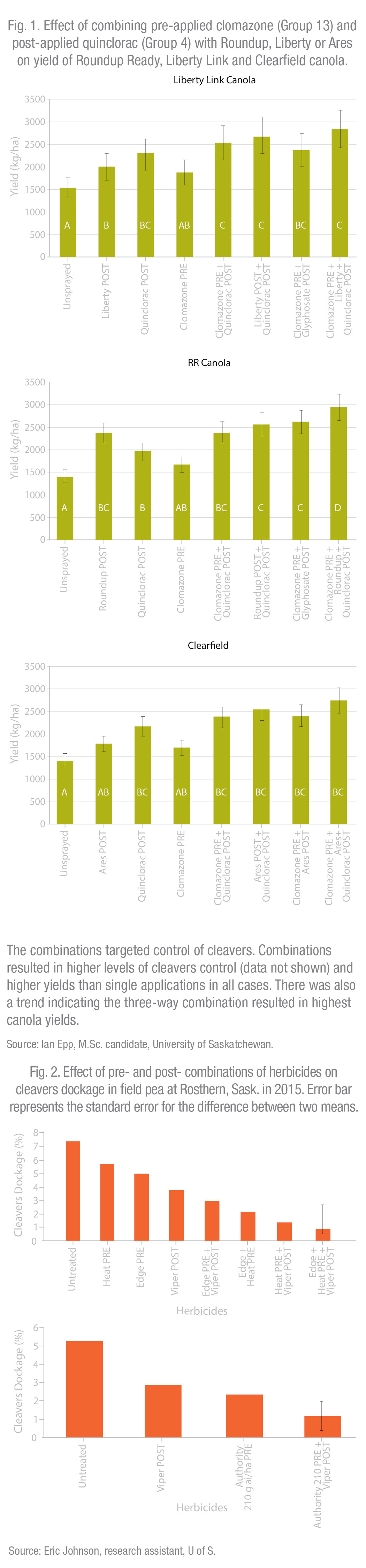

In the studies on cleavers weed control in canola, the researchers used three different modes of action – applying clomazone pre-emergent, then followed by either Clearfield, Roundup or Liberty tank mixed with quinclorac. “Even with the Roundup system, which is already pretty effective on cleavers, we found that using three different modes of action provided weed control benefits, and some yield benefits which totally surprised us,” Johnson notes. (See Fig. 1.)

The team also did studies on managing Group 2 resistant cleavers in field pea. “What we found was that if we put a pre-emergent down, that suppressed the cleavers somewhat. But then we came in and followed with a post-emergent, and we ended up with better than 80 per cent control.” (See Fig. 2.)

Going forward, the U of S is starting some work on managing Group 2-resistant wild mustard and Group 2-resistant kochia in lentil.

The big picture of herbicide layering

Brenzil says herbicide layering has some merit for everyone. “What the U of S research has found is that if you have control taking place right at the point where the weed is germinating [with the pre-emergent], you’re going to get better yield response out of your crop, rather than waiting for the three- or four-leaf stage when there’s already been some competitive effect of that weed on that crop,” he notes.

“By having a soil active, even if it’s not doing a fantastic job of controlling the weeds, it’s suppressing the influence of those weeds on that crop, and you’re getting a bit of a yield bump by having herbicide in the soil along with your foliar product that’s coming a little later.”

An added bonus, Brenzil adds, is that by using a herbicide layering program, you’re making a pre-emptive strike against herbicide resistance. “It’s a good management tool for controlling some of those weeds that may not necessarily be that responsive to one herbicide for effective management, such as wild oats and cleavers.”

At the Herbicide Resistance Summit held March 2 in Saskatoon, Jason Norsworthy made a comment about the “treadmill” of using one weed chemistry and the very real threat of developing herbicide resistance as a result. Brenzil explains: “If you use one chemistry to death and then you allow your weed populations to get very high again, then you’re just starting from square one to select for the next Group that you’ll overuse, and so on and so on, until you paint yourself into a corner and there are no herbicide options left. At this point, the only management option left will be seeding the field to a forage crop and cut for hay until the seedbank is exhausted.”

With herbicide layering, “If you’ve got your soil active products on the ground, then you come in with your foliar and you’ve got a mix of two foliars that could still control that same weed – now you have three active in there of different families,” he adds. “You avoid that overuse and you don’t allow selection pressure to accumulate.”

This story originally appeared in the June 2016 issue of Top Crop Manager West.