Features

Agronomy

Weeds

Herbicide resistance in Ontario: An ever-evolving affair

Exploring the history of herbicide resistance in Ontario and recent developments for solutions.

August 1, 2021 By François Tardif

Herbicide resistance is evolving in Ontario. François Tardif, professor of plant agriculture at the University of Guelph, discussed how herbicide resistance develops and best practices to manage it at the Top Crop Summit, Feb 23-24, 2021.

Herbicide resistance is a form of adaptation. Herbicide resistance happens at the population level. Individual plants are not changing. Rather, the type of individuals in a population are changing. Herbicide application selects for individual weeds that are resistant to that herbicide. Over years of repeated herbicide application, the weeds that are resistant to the herbicide survive and multiply to become the dominant population.

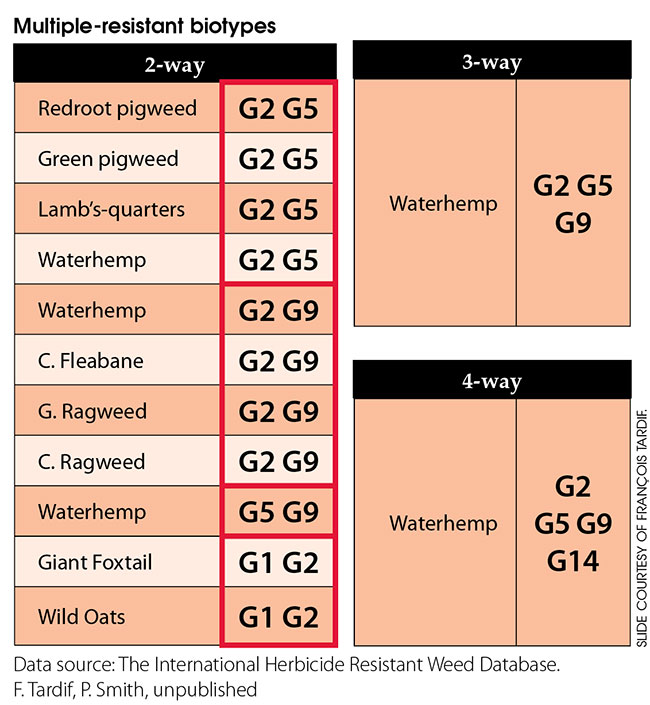

The first documented resistant weed in Ontario was wild carrot that was resistant to 2,4-D found in 1957. In 1973, lamb’s-quarters resistant to atrazine herbicide was identified. The first glyphosate-resistant weed, giant ragweed, was confirmed in 2008. In 2017, four-way resistant waterhemp was confirmed. There are now 38 herbicide-resistant weed biotypes, in 21 weed species and resistance to seven different herbicide groups.

Multiple-resistant biotypes have become common.

In Canada, 119 resistant biotypes have been identified in 38 weed species and to 10 different herbicide groups.

The way weeds reproduce has a big impact on how fast multiple resistance develops. While the majority of weeds are self-pollinating, cross-pollinating weeds develop multiple resistance faster. Cross-pollinating populations are more variable and they shuffle genes each generation. This means that cross-pollinating weeds like waterhemp develop resistance much faster than self-pollinating weeds.

The challenge for farmers is to find an increasing diversity of weed control methods while addressing the need for soil conservation, time management and profitability. When applying herbicides, the use of effective mixtures with different modes of action is necessary – but make sure you aren’t over-relying on herbicides.

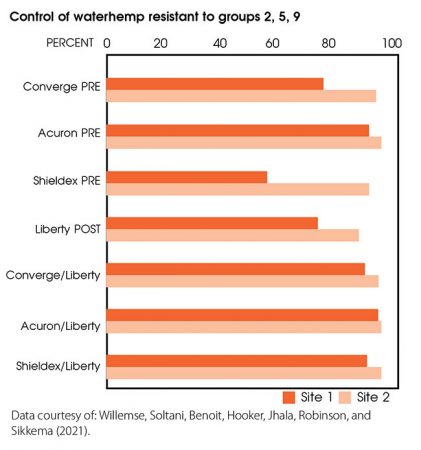

Research by Willemse et al., published in 2021, looked at herbicide mixtures to control waterhemp that was resistant to Groups 2 + 5 + 9. Several herbicide mixtures were able to achieve greater than 95 per cent control through the use of effective modes of action.

Diversification of cropping systems will also be required to manage herbicide resistance. This diversity may include the use of cover crops, the manipulation of row width and density to improve crop competition, and cultivation for weed control.

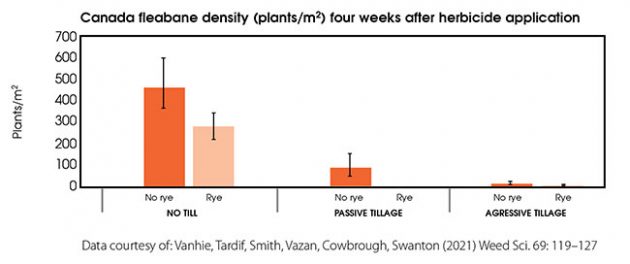

Research has found that the use of a rye cover crop can reduce Canada fleabane density. And the rye cover crop was even more effective in reducing Canada fleabane with the introduction of tillage.

Research also showed that a rye cover crop improved the effectiveness of a herbicide application on Canada fleabane. Four weeks after applying saflufenacil, the combination achieved almost complete control, and was significantly better than herbicide application without a rye cover crop.

In conclusion, the rise of cross-pollinated multiple herbicide resistance will make weed control more difficult. And we can’t count on many new modes of action to be registered to help control herbicide-resistant weeds. Introducing more diverse weed management is the only way out.