Features

Agronomy

Diseases

Goss’s wilt moving in

Goss’s wilt bacteria are likely to become permanent residents on every cornfield in Western Canada in the next decade or two. Major damage can be prevented, but the bacteria are here to stay.

When severe, the bacterial disease can slice 40 bu/ac off yield, according to Manitoba Agriculture, Food and Rural Development (MAFRD) plant pathologist Vikram Bisht.

Growers will find they have a few important tools for coping with the new disease. These include cultivating and burying corn residue, rotating fields into other crops, and selecting corn hybrids with good ratings for tolerance to Goss’s wilt.

Blight symptoms

A good starting point, Bisht says, is to get the name right.

“Goss’s wilt is really Goss’s bacterial wilt and leaf blight,” he says. “The leaf blight phase is the only phase we have seen at this point. We may have missed finding the wilting phase.”

The bacterial cause is known as Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. Nebraskensis (CMN). It is one of about a dozen bacterial diseases known to occur in corn. Worldwide, maize crops also are subject to many fungal diseases, plus many viral diseases and various parasitic nematodes.

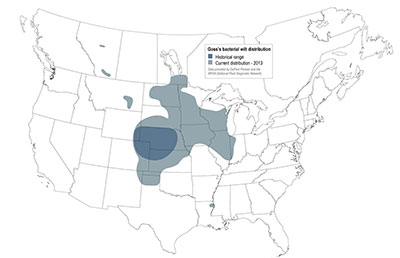

According to the University of Nebraska, it was first identified in three fields in central Nebraska in 1969. It was observed in other U.S. states, but was not a serious problem until recent years. It re-emerged in 2006, particularly in the tri-state region of western Nebraska, northeast Colorado and southeast Wyoming.

Plant wounding due to severe weather and a local history of the disease are likely to blame for early development. Yield impact worsens the earlier that it develops and in proportion to the amount of leaf area affected by the bacterial lesions, according to Nebraska pathologists. It can lead to stand loss, plant death and major yield loss. It can develop even in resistant hybrids that have been wounded substantially.

Nobody beyond the tri-state region was looking for Goss’s wilt after the 2006 reemergence, but routine corn surveillance led to suspicions.

Officially, it was confirmed in 2009 in two fields near Roland, Man. Today it is broadly spread throughout Manitoba’s corn production zone as far west as Holland and north to Portage la Prairie. In 2013 it was also confirmed in five Alberta cornfields (near Lethbridge and Taber).

“We don’t know how we got it. Maybe it came with seed. Maybe it came up on thunderstorms or with machinery,” says Bisht. If you enter a field where you suspect Goss’s wilt may be present, be sure to remove any soil or plant matter from boots, wheels or implements before leaving that field, as the disease can be transferred by rain, wind and soil, and by residue moving from field to field.

DuPont Pioneer began doing field surveys soon after the disease was confirmed in Manitoba. Bisht says the disease was confirmed in 80 per cent of the inspected fields, or more, in 2011, 2012 and 2013.

“Its presence does not mean a yield reduction. It just means that at least one plant had the disease in that field,” he notes. “In coming years I think yield losses will be showing up in many places. The disease becomes an issue when we have thunderstorms with strong winds. In severe cases the loss of yield can be over 60 per cent.”

Symptoms are classic, when you know what to look for. Initially, look on the leaves for small, dark brown, slightly elongated freckles. Some of these lesions may be oozing where there was a leaf injury. Other diseases may produce similar freckles but oozing is associated only with the leaf blight phase of Goss’s wilt. Symptoms are most likely to emerge a few days after a strong thunderstorm.

A bit later, a small patch or two in a field may appear to be singed or drying up while the rest of the field looks healthy. Leaves may have a slight brown discoloration on top. It can spread quickly after that.

“The initial few spots can join with other spots if the disease becomes very serious. The leaves will dry up in a patch very, very quickly while the stalks appear to be good. It can happen in the course of two weeks, especially if there has been a fair amount of moisture and dew,” says Bisht.

The bacteria migrate into stalks, in time, where they can plug the plumbing system. Discoloration will appear in a cross-section of a stalk.

Once established, the bacteria causing Goss’s wilt survive and reproduce on the corn residue. If that is buried and decaying, the bacteria also can survive on at least two host grasses – green foxtail and barnyard grass.

The bacteria will move to adjacent plants on splashing rain; they will move to an adjacent field on wind gusts, or simply blow along onto adjacent land after harvest. An infected field should be kept out of corn production as long as possible or planted to resistant corn hybrids. Fields adjacent to an infected field probably will have the Goss’s wilt bacteria in the following year.

Lab analysis

Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food (OMAF) pathologist Albert Tenuta has been working with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada to monitor for Goss’s wilt and other corn diseases in Ontario. It has not been found yet in Ontario or farther east in Canada but it is close – it’s been found in southern Michigan and in Indiana.

“Being a bacterial disease, the pathogen is very difficult to identify in the field so it is best to submit a sample for lab analysis. This is especially important in areas where the disease has not been detected before” says Tenuta.

Growers should be cautious about using immuno-strip test kits that are offered for field testing, he warns. These kits are not specific to CMN but instead identify a closely related bacteria that is common to tomatoes.

“The test will often give false positives. It’s not specific enough for the Goss’s bacteria in corn. We find false positives in Ontario quite a bit. Every time we do a followup in the lab, it turns out to be a negative,” he says.

While fungicides are ineffective against the bacterial disease, the new disease can be mistaken for other diseases where fungicides are effective. It points to the need for lab analysis and importance of proper identification. “If a grower thinks he has northern leaf blight, and applies a foliar fungicide, it won’t control your Goss’s wilt, which means a potential waste of money,” says Tenuta.

New hybrids

Seed companies are moving quickly to improve genetic resistance to the bacterial attack in new corn hybrids. Quite a few hybrids with good resistance are available already from DuPont Pioneer and Monsanto. More are coming.

“The level of resistance may be differing,” warns Bisht. “Sometimes the pathogen is different, so what is resistant in one place may not be resistant in another place (to a different race of the bacteria). It is important to discuss that with the seed suppliers, too, and we need to figure that one out for infections in Manitoba and Alberta.”

According to Wilt Billing, area agronomist for DuPont Pioneer in eastern Manitoba, five years ago “if you took every corn hybrid sold in Manitoba, only a few products would carry moderate levels of resistance [to Goss’s wilt]. Averaging the products available, the overall resistance rating would be 3 (or poor) on a scale of 1 to 9.” Today, Billing says, the average hybrid resistance rating to Goss’s wilt in DuPont Pioneer seed products has increased up toward a 5 on that scale. “Our strongest products would be rated 6’s and 7’s. A 7 would be considered resistant.”

Billing says new products were developed and identified in Manitoba using nursery screening, molecular markers and field verification trials. “Where fields are known to have Goss’s wilt, we’re incorporating our most resistant lines very successfully. Those growers are not seeing any yield impact when planting hybrids with improved resistance to Goss’s wilt.”

Goss’s wilt surveys, led by Billing from 2010 through 2013, found the disease throughout the traditional corn growing area of Manitoba. In 2013 it was found northeast of Winnipeg, near Portage la Prairie and as far west as Holland, Man.

Bruce Murray, eastern Manitoba agronomist for DeKalb, says the company has tested for Goss’s wilt in Nebraska. “We’re a large company, just starting to get our heads around Goss’s wilt in Manitoba,” he notes. “A big chunk of our lineup is coming back as tolerant, and we did see that in the field this year, [even though] we were seeing more Goss’s wilt in our plots.” The DeKalb 30 Series corn hybrids are an 80-day corn that has very strong tolerance to the disease, says Murray. Three other DeKalb hybrid lines – 26, 27 and 31 – are nearly as tolerant to the bacterial attack.

Responding to intense grower interest, Murray says Monsanto initiated a full-time testing and development program in Manitoba in early 2013, as an extension of its effort at the former DeKalb research farm at Glynden, Man. He predicts that, “It’s going to come to the point, in a few years, you’re going to have to have that tolerance for resistance or you’re not in the game.”

Current distribution of Goss's wilt across North America (map courtesy of DuPont Pioneer, Johnston, Iowa).

February 18, 2014 By John Dietz

Goss’s wilt has spread throughout Manitoba’s corn production zone as far west as Holland and north to Portage la Prairie. In 2013 it was also confirmed in five Alberta cornfields (near Lethbridge and Taber) Goss’s wilt bacteria are likely to become permanent residents on every cornfield in Western Canada in the next decade or two.

Goss’s wilt has spread throughout Manitoba’s corn production zone as far west as Holland and north to Portage la Prairie. In 2013 it was also confirmed in five Alberta cornfields (near Lethbridge and Taber) Goss’s wilt bacteria are likely to become permanent residents on every cornfield in Western Canada in the next decade or two.