Features

Diseases

Soybeans

Forewarned is forearmed: Soybean cyst nematode in Manitoba

Early detection of soybean cyst nematode in Manitoba gives growers a better chance to fight back.

December 27, 2019 By Carolyn King

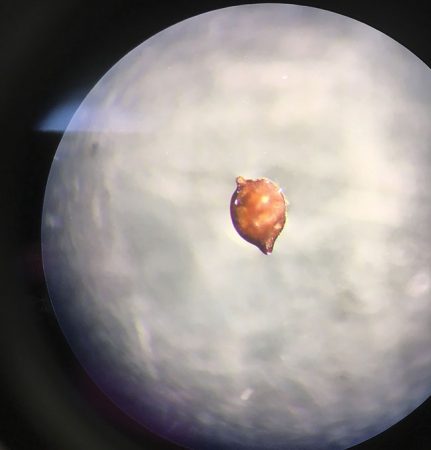

The little pinhead-sized, white cysts on this soybean root are soybean cyst nematodes.

Photos courtesy of Nazanin Ghavami Shirehjin, University of Manitoba.

The little pinhead-sized, white cysts on this soybean root are soybean cyst nematodes.

Photos courtesy of Nazanin Ghavami Shirehjin, University of Manitoba.

Careful surveying has determined that soybean cyst nematode has now arrived in Manitoba and is present at very low levels in some isolated fields. This soil-dwelling, microscopic roundworm has been spreading across the soybean-growing areas of North America. Manitoba’s really early detection gives growers the opportunity to take steps to slow the pest’s spread in the province.

“Soybean cyst nematode is ranked as the number one disease agent for soybean in North America,” says Mario Tenuta from the University of Manitoba, who has been leading the surveys.

“It is a serious yield robber of soybean grain in areas of North America that have a history of soybean production, which is most of the soybean-growing areas in Canada and the U.S. Yields losses can vary from zero to five per cent up to as high as 30 or 40 per cent in severe cases under dry weather conditions.”

Soybean cyst nematodes (SCN, Heterodera glycines) attack the roots of soybean plants, stealing nutrients, impeding water uptake and interfering with nodulation. The nematodes also reproduce on the roots. Each cyst starts as an adult female nematode swollen with eggs while attached to the root to feed. A cyst is about the size of a pinhead, and it changes colour from white to yellow and then to brown or black as the female completes her life cycle and dies. The hardened cyst, which eventually falls off the root, provides protection so the eggs can survive up to several years in the soil, until conditions are right for hatching.

“This disease doesn’t outright kill the soybeans; the plants survive but produce lower yields,” Tenuta notes. “So the problem can go for a long time without being really recognized by farmers. This is probably its most detrimental characteristic, in that it can be ignored up to a point and then it delivers a serious hit on yield.”

When SCN first arrives in a field and its population is still very low, it doesn’t produce any aboveground symptoms in the crop. As its population grows, it starts causing symptoms like stunted plants, yellowing leaves and poorer yields, but these impacts are easy to confuse with symptoms of other crop problems. On top of that, it also takes a while for the SCN population in a field to become high enough to be detected in routine soil tests in commercial labs.

Another challenging aspect is that the nematode spreads from field to field by the movement of infested soil. That includes soil on field equipment, vehicles, boots and clothing, and soil carried by wind, water or even birds. So it is difficult to completely stop the nematode’s spread to new fields. And once SCN arrives in a field, it is very tough to eradicate.

And once SCN arrives in a field, it is very tough to eradicate.

The nematode’s damage to soybean roots can also facilitate infection by other pathogens. In particular, the spread of SCN is closely associated with the spread of soybean sudden death syndrome, a yield-limiting fungal disease. Tenuta says, “There is no doubt in my mind that as soybean cyst nematode levels increase in more fields in Manitoba, soybean sudden death will increase as well.”

A needle in a haystack

Tenuta knew it would only be a matter of time before the pest arrived in Manitoba – SCN has been in Minnesota since 1978 and in North Dakota since 2003, and it has been spreading in both states. So he and his research group at the University undertook a series of surveys to watch for the nematode’s arrival in the province.

“We have done three soybean cyst nematode surveys, starting in 2012, with the support of the Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers, in collaboration with Manitoba Agriculture and us at the University,” Tenuta explains. The surveys focused on the region of Manitoba with the greatest potential for early arrival of SCN. This region includes areas with a long history of soybean production and that are also close to the U.S. border and/or along the Red River. The survey team contacted soybean growers in this region and obtained permission to sample their fields. He says, “All the farmers said, ‘Yes, no problem.’”

Over the course of the three surveys, the team sampled 106 fields in 18 rural municipalities. Using a soil probe, they sampled each field’s high-risk spots – such as field entrances, depressions, and areas near watercourses – taking dozens of cores per field.

They analyzed those samples in the lab for the presence of the nematode. In this analysis, they used a U.S. Department of Agriculture cyst extractor, which floats, sifts and traps the little cysts onto a screen. This equipment allowed Tenuta’s group to analyze large, 5-pound soil samples. “Since we were looking for the first occurrence of the nematode in Manitoba, we were expecting very low levels of cysts in the soil so we wanted to process more soil.”

The first two surveys, which were carried out in 2012-13 and 2014-15, found no SCN cysts.

“Then in the latest survey [which started in fall 2017], we found four fields with low levels of SCN cysts. The identification was confirmed with DNA tests,” he notes.

“Then in the latest survey [which started in fall 2017], we found four fields with low levels of SCN cysts. The identification was confirmed with DNA tests,” he notes.

One field was found in each of four rural municipalities: Emerson-Franklin, Montcalm, Rhineland, and Norfolk Treherne. Since these locations are fairly far apart, it may be that SCN is present in some other fields in the region that were not surveyed.

Tenuta’s group was very careful in conducting the soil sampling and analysis and in re-sampling the soil in the SCN-positive fields to confirm the nematode’s presence. “As well, this year, my PhD student Nazanin Ghavami Shirehjin visited the field that had the highest level of the cysts in the soil samples; the producer was growing soybean in that field this year so Nazanin could check the roots for cysts. She found some cysts and visually confirmed that they were soybean cyst nematode. The nematode was at very low levels on the roots, as we expected.” The soybean crop in this field didn’t have any visible symptoms of SCN infection.

Cyst numbers in all four Manitoba fields were extremely low. For instance, the surveyed field with the most SCN cysts had just 20 cysts per five pounds of soil. Tenuta explains that in some Ontario soybean fields where the pest has been present for several decades, there can be 3,000 to 4,000 cysts per five pounds of soil.

Developing a better, faster test

Long, tedious lab procedures are currently used for SCN analysis – first to find cysts in soil samples, then to check that those cysts are Heterodera glycines and another nematode species, and then to count the SCN cysts. These steps include things like hand sorting of the debris on the screens, careful visual examinations of the tiny cysts, and then DNA techniques to confirm the species identification.

So, as part of his current SCN project, Tenuta and his group are developing some improved molecular methods to identify and quantify SCN levels in soil samples. He says, “The idea is to make the testing a lot faster and more economical so diagnostic labs can provide a quicker turnaround time with lower costs to the farmers. We also want to see if a molecular method can provide a much more robust test, because there can be user variability with the traditional methods.”

Ghavami Shirehjin is working on these methods with colleagues in Ontario, including Tenuta’s brother Albert, who is the field crop pathologist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

Slow the spread of the pest

“I believe we have probably the earliest detection of soybean cyst nematode compared to other soybean-growing areas because we have been really diligent and because we had the support of the Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers to do surveys early on,” Tenuta says.

“I’m hopeful that this early detection gives Manitoba an advantage to get the word out to growers so they can take steps to really slow the nematode’s spread. In other soybean growing regions, the nematode has moved fairly quickly as soybean years in a field increase.”

Tenuta recommends that Manitoba soybean growers be proactive, taking action while SCN levels are still low.

“The best advice is to be aware of the nematode, to know about it and particularly know how it spreads. So try to avoid bringing soil into a field from other fields. Knock off the soil, then pressure-wash field implements. Minimize traffic onto the field with your vehicle or boots. Wash your vehicle, and wash your boots or wear plastic booties.”

Crop rotation is also important. He says, “Make sure you don’t have tight soybean rotations. Use a rotation with soybean once in four years or once in three years [with non-host crops in the rest of the rotation].” The nematode requires a host plant – such as soybean, dry edible bean, field pea and other legumes – for reproduction, so a longer rotation gives more time for the eggs in the cysts to die.

“Make sure you don’t have tight soybean rotations. Use a rotation with soybean once in four years or once in three years [with non-host crops in the rest of the rotation].”

“And I encourage growers to choose resistant soybean varieties for their rotations. The Manitoba Seed Guide will tell you which varieties are resistant to soybean cyst nematode.”

Tenuta also recommends scouting soybean fields for SCN. Look for areas with dwarfed plants, delayed canopy closure, and yellowing patches. And in July and August, check the roots of some soybean plants in the high-risk areas of your field, like the field entrance, and any areas showing possible aboveground SCN symptoms. To examine the roots, use a shovel to gently lift up the plant with its roots and put the roots in a bucket of water, to avoid knocking the cysts off the roots. Use a magnifying lens to examine the roots. Look for little pinhead-sized, lemon-shaped, translucent to white cysts.

If you find what you suspect are SCN cysts, contact Manitoba Agriculture or the Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers.

Funders of Tenuta’s SCN research include the Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers, Western Grains Research Foundation, and Manitoba Agriculture through federal-provincial agreements for agricultural research including Growing Forward 2 and the Canadian Agricultural Partnership. Syngenta and NorthStar Genetics provided seed for some of the project’s growth chamber and greenhouse work.