Features

Agronomy

Cereals

Fighting fungus with fungus

A new species of fungus native to Saskatchewan is being developed into a biopesticide to fight another fungus, Fusarium.

Fusarium causes fusarium head blight (FHB), the most destructive fungal

disease of wheat and barley in Canada. This devastating and

difficult-to-control disease causes severe yield loss and produces

toxins that limit the use of the infected grain for food and feed.

September 21, 2010 By Carolyn King

|

|

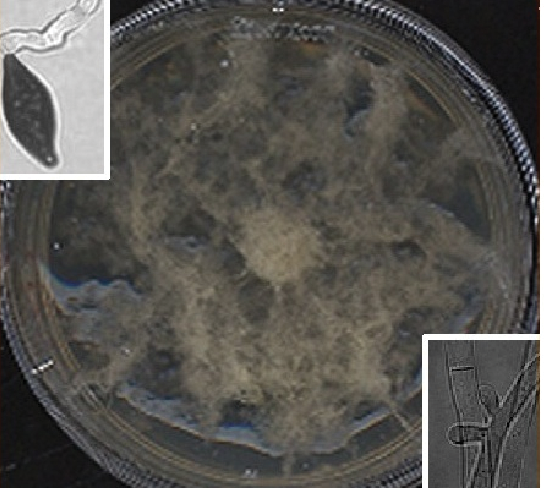

| Sphaerodes mycoparasitica is a species of fungus that naturally parasitizes the Fusarium fungus. (Upper left inset shows its spore germination; lower right inset shows its contact structures parasitizing a Fusarium cell). Photo courtesy of Dr. Vladimir Vujanovic, University of Saskatchewan.

|

A new species of fungus native to Saskatchewan is being developed into a biopesticide to fight another fungus, Fusarium.

Fusarium causes fusarium head blight (FHB), the most destructive fungal disease of wheat and barley in Canada. This devastating and difficult-to-control disease causes severe yield loss and produces toxins that limit the use of the infected grain for food and feed.

Fusarium’s recently discovered attacker is called Sphaerodes mycoparasitica. This parasitic fungus, or “mycoparasite,” is a natural parasite of Fusarium. It was discovered by Dr. Vladimir Vujanovic, a microbiologist at the University of Saskatchewan. “No one had paid much attention previously to mycoparasites on Fusarium,” he says.

So when he arrived in Saskatchewan in 2005, he started examining the mycoparasites in samples from Saskatchewan wheat fields. Vujanovic developed a way to isolate Fusarium from the samples and then pick up mycoparasites from that strain of Fusarium. He identified several new mycoparasite species, and examined how the various mycoparasites interacted with Fusarium. He chose Sphaerodes mycoparasitica as the species with the best potential for use as a biopesticide to control Fusarium.

According to Vujanovic, Sphaerodes mycoparasitica offers some important advantages compared to other fungi that are currently used as biopesticides to control plant pathogens. One is that Sphaerodes mycoparasitica specifically attacks Fusarium, and not other fungi. He says, “Many other microbial biopesticides are based on groups of mycoparasites that are generalists. That is, they fight not only with the pathogen but with all the beneficial microbes in the surrounding environment.”

Another important advantage of Sphaerodes mycoparasitica is that it attacks more than one species of the Fusarium genus at the same time in the same sample. Vujanovic explains, “Fusarium head blight is caused by a Fusarium species complex; it is not just one type of Fusarium that is involved in fusarium head blight, but several species, including Fusarium graminearum and Fusarium avenaceum. Our mycoparasite is specific to Fusarium at the generic level.”

The mycoparasite’s mode of attack depends on which particular Fusarium species it is attacking. He says, “For example, in the case of Fusarium graminearum, which is the most important cause of FHB, the mycoparasites will first attach on the surface and then absorb nutrients from the cells of Fusarium. Or they will penetrate intracellularly, and the mycoparasites will be propagated inside the Fusarium cells.”

|

|

| An inoculant from a Saskatchewan fungus is being developed as a way to fight Fusarium head blight, a devastating and difficult-to-control disease of wheat and barley. Photo courtesy of Bruce Barker. |

Developing an inoculant

The mycoparasites do not necessarily prevent Fusarium outbreaks under natural conditions. Vujanovic says, “In nature, the mycoparasites get more abundant as Fusarium gets more abundant. So they stop Fusarium but on the peak of its development and that is too late for the producers, it is too late for the crop yield. However if we pre-inoculate seeds or apply the mycoparasites before the Fusarium attacks, then we can prevent the Fusarium outbreak. So we are working on the biotechnology to apply the mycoparasites in advance.”

Vujanovic and his research team are now developing a Sphaerodes mycoparasitica inoculant. His team includes a plant pathologist and a soil microbiologist, as well as researchers from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, who are working on the inoculant formulation.

He says the biopesticide is close to being ready for commercialization. “We have already tested the mycoparasites against different Fusarium species and Fusarium mycotoxins in vitro (in the lab), in the phytotron growth chambers that allow precise control of temperature, light and humidity, and in a greenhouse system.”

Their work indicates the inoculant is able to stop Fusarium itself and toxin production by Fusarium.

The researchers are now testing the inoculant at two locations in Saskatchewan. They are assessing its efficiency under the field conditions, its impact on the environment, and its effects on Fusarium toxicity.

The University of Saskatchewan has patented this discovery, and it is looking for industry partners in the commercial production of the inoculant. “I think many, many agricultural producers will really benefit from this product because there are no efficient management practices against Fusarium and no resistant cultivars. Fusarium, particularly Fusarium graminearum, is aggressively spreading across the Prairies. I think it is a very urgent matter to try to stop the progress of Fusarium in Western Canada,” he notes.

According to Vujanovic, the mycoparasitic inoculant represents the way of the future for controlling plant pathogens. “In many regions, the use of chemical pesticides against pathogens has already been stopped. I think very soon people will try to replace chemical pesticides with biological pesticides. And those biological pesticides will mostly use indigenous species, such as this one. The microbial biopesticides available now usually use exotic species from other countries to apply on our fields. From my point of view, it is better to use indigenous species from this region to develop a biopesticide, and to apply it in the same ecozone.”

He adds that organic growers are also interested in his work. “They are interested in having an indigenous species, not probably to apply it directly, but to take the knowledge and understanding of the diversity of mycoparasites in the field and try to adapt their management in a way that supports mycoparasites against Fusarium.”

Vujanovic’s work to develop the biopesticide is supported by Saskatchewan Agriculture’s Agriculture Development Fund. His earlier research to gain a fundamental understanding of mycoparasite diversity and mode of action against plant pathogens was funded by a discovery grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.