Features

Environment

Field boundary habitats: The ecological diamonds in the rough

Understanding the role of field boundary habitats.

December 28, 2019 By Jennifer Bogdan

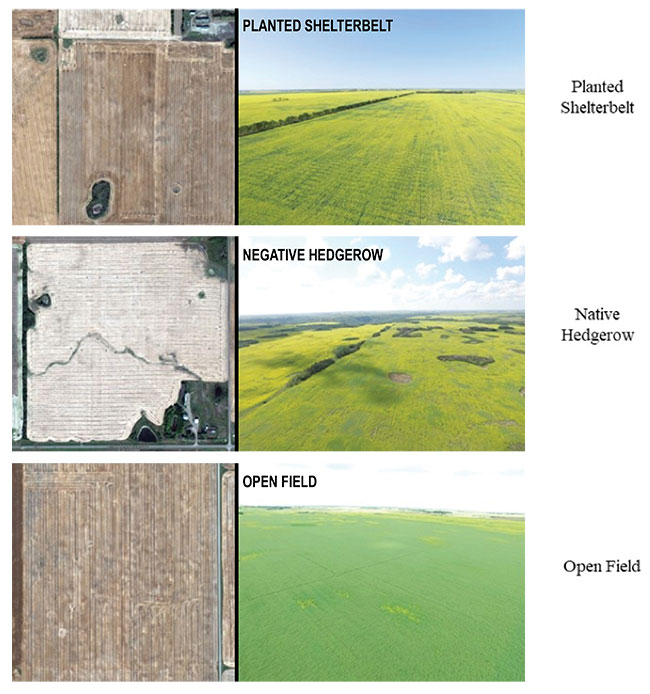

Examples of field boundary habitat types (planted shelterbelt and native hedgerow) aused to compare with open field sites in the FBH project.

Photos courtesy of Shathi Akhter.

Examples of field boundary habitat types (planted shelterbelt and native hedgerow) aused to compare with open field sites in the FBH project.

Photos courtesy of Shathi Akhter.

A drive through the Saskatchewan Prairies shows exactly what one may envision when it comes to crop production in the province: ocean-like expanses of swaying cereal fields, broken up by yellow canola and blue flax fields, all intertwined with fields of lush green pulse crops. The cropland stretches on for miles, making it almost believable that you actually could watch your dog run away for three days, as the joke goes. The colourful pattern of fields resembles the patches of a giant quilt – but what exactly is in the stitching that holds it all together? A new study is taking a much-needed look between the fields, by exploring field boundary habitats.

Shathi Akhter, research scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Indian Head, Sask is assessing the role of field boundary habitats in agro-ecosystems and why producers should be concerned.

“Field boundary habitats (FBH) are non-cropped areas adjacent to annual crops. There has been little documented research on the ecological and economic benefits of FBH in promoting crop productivity and ecological diversity in intensely cropped agricultural landscapes in Saskatchewan. This project attempts to measure the benefits or services provided by FBH, such as increased pollination from native bees and predation of flea beetles and other pests by carabid beetles, to determine whether it is advantageous for producers to maintain these habitat areas on the landscape,” she explains.

“This project attempts to measure the benefits or services provided by [field boundary habitats], such as increased pollination from native bees and predation of flea beetles and other pests by carabid beetles, to determine whether it is advantageous for producers to maintain these habitat areas on the landscape.”

Examples of FBH include shelterbelts, native hedgerows, road allowances, wetlands, and streams. These natural habitats support thousands of species of native plants, insects, birds, mammals and reptiles. As part of the ecosystem, FBH also play a role in pollination, natural pest control and drought and flood mitigation. “At present, we classify these ecosystem services as non-market good and services. Therefore, it is difficult for crop producers to identify these services and include them in their farm operation management decisions,” Akhter says.

One of the main objectives of the project includes determining the risks and benefits of FBH to the neighbouring field crops. This assessment includes measuring crop yield and quality, as well as pollinator, beneficial insect, and bird biodiversity. Soil parameters, such as quality, moisture, and the microbial community, will also be studied. After the data is analyzed, Akhter’s team will put forward best management practices that producers can use to improve crop yield and quality, while simultaneously supporting pollinators and other beneficial species.

While honeybees seem to hold the pollinator spotlight, Saskatchewan is home to 350 species of wild bees. However, some of these species, like bumblebees, are decreasing sharply in population. Many of the native bees are solitary and nest in undisturbed areas that also provide them with a season-long food supply and overwintering sites. It’s not surprising that field boundary habitats are critical to the survival of these important pollinators.

Microbial sampling for field boundary habitat project.

Another objective of the project will be to assess the risk of weeds spreading from the FBH into the adjacent crop. Field boundaries can be reservoirs for unwanted plants; the researchers will study the soil seed bank from the boundary and extending into the crop, so any weed spread potential can be quantified.

Field boundaries can be reservoirs for unwanted plants; the researchers will study the soil seed bank from the boundary and extending into the crop, so any weed spread potential can be quantified.

When all of the data has been collected, a cost-benefit analysis of FBH will be performed. Producers will then know the economic impact of plant and animal diversity, and microclimate effects on crop yield and quality. Taking it one step further, the project will summarize the overall relationship of FBH on crop yield on a large-scale, regional basis.

Akhter also points out the importance of the societal benefits provided by FBH. Native prairie, natural habitats, and wetlands are all critical components of a healthy ecosystem, aiding in functions such as carbon sequestration and water filtration. Research that facilitates more in-depth knowledge of FBH can also help with policy development in the future, which can potentially add greater benefit for producers.

Early results look promising

Preliminary data from research conducted in 2017 and 2018 using canola fields found that fields with FBH produced three per cent higher oil compared to open fields. The thousand seed weight of canola also increased in the FBH areas. These years also were drier with low precipitation, yet the benefit of FBH remained. In addition, FBH sites had significantly greater population and diversity of pollinators, carabid (ground) beetles, birds and soil microbes compared to open field sites. Some locations had up to 20 times more carabid beetle populations in the FBH sites than in the open fields. Carabid beetles are general predators, consuming cutworms, bertha armyworm larvae, lygus bugs, flea beetles, pea leaf weevils, and many other insects.

FBH sites had significantly greater population and diversity of pollinators, carabid (ground) beetles, birds and soil microbes compared to open field sites.

Data from 2019 will soon be compiled with the previous two years and effects on yield will be more closely examined. Akhter hopes to gain additional funding to extend the project to a five-year study, where they plan to collect three years of continuous data from the same sites in a canola-wheat-pea rotation.

Overall, Akhter’s research hopes to encourage producers to consider the hidden ecosystem benefits before removing habitats that are often viewed as wasted land that could be farmed instead.

“Habitat destruction associated with the conversion of natural areas to cropland, drainage of wetlands, and removal of shelterbelts and natural field barriers to accommodate larger machinery have contributed to a loss of diversity. The FBH project will provide recommendations for managing these critical areas to mitigate the further loss of suitable habitat or to create new habitat by implementing best management practices,” she says.