Features

Agronomy

Weeds

Weeds to watch: Preparing for the arrival of Palmer amaranth

Grows more than two inches per day. Produces over one million seeds per plant. Grows 10 feet tall. Resistant to at least four different herbicide groups in the U.S. No wonder 200 American weed scientists in 2017 ranked Palmer amaranth the most troublesome weed in broadleaf crops, fruits and vegetables.

March 31, 2018 By Bruce Barker

While Palmer amaranth has not yet crossed the 49th parallel, given the rapid spread in the U.S., it is likely just a matter of time.

“I do think that it is possible that Palmer amaranth will appear in Ontario agricultural fields, but, I will never predict when – it could be next year or decades in the future,” says Peter Sikkema, professor of weed management at the University of Guelph Ridgetown campus.

Palmer amaranth was first identified in southeastern U.S. cotton fields in 2005. Today, Palmer amaranth is found in nearly every part of the U.S. except for the northwest and extreme northeast. The states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota and Wyoming have so far avoided the creeping invasion.

“I am convinced southern Ontario will soon have glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth,” says Jason Norsworthy, professor and endowed chair of weed science at the University of Arkansas.

In North Dakota, weed scientists have been proactive in providing farmers with information on Palmer amaranth, naming it weed of the year in both 2014 and 2015.

“I think the genetic diversity of Palmer amaranth will allow it to ‘survive’ in North Dakota and Canada. Our climate may not favour the two-to-three inches growth per day as in the south but it can survive,” says Richard Zollinger, extension specialist and professor of weed control at North Dakota State University.

Palmer amaranth is thought to have spread in the U.S. in multiple ways. It was introduced into Michigan with cotton seed used in dairy rations that contained Palmer amaranth seed. The weed was subsequently spread with manure. Other mechanisms may include custom combines carrying seed, movement of contaminated seed, hay or forage, transport by ducks and other waterfowl, as well as water flow.

Water flow may pose the greatest risk for Manitoba farmers in the Red River Valley. Palmer amaranth seed is light and floats on water. Flooding of the Red River may eventually move the weed up through North Dakota and into Manitoba.

Why so threatening?

Several traits make Palmer amaranth a real threat for farmers. Yield loss has been measured at 78 per cent in soybean and 91 per cent in corn in the U.S.

Sikkema says in Canada, yield loss will depend on several factors including relative time of crop and Palmer amaranth emergence, Palmer amaranth density, adaptation to Canadian environmental conditions, and environmental conditions in each growing season.

“Using glyphosate-resistant waterhemp as an example [a related amaranthus species], the yield losses due Palmer amaranth interference will vary from less than 10 per cent to greater than 75 per cent in both corn and soybean,” Sikkema says.

Fast growth and prolific seed production are important, but because the weed has both male and female plants, it reproduces by cross-pollination. This means the weed has wide genetic diversity and may help contribute to its adaptation to new areas.

Additionally, that wide genetic diversity means herbicide-resistant populations can be quickly selected with frequent herbicide use. In the U.S., Palmer amaranth quickly developed glyphosate resistance, primarily because of tight rotations of Roundup Ready crops. Now, Palmer amaranth has developed stacked resistance to ALS resistance (Group 2), DNA resistance (Group 3), glyphosate resistance (Group 9) and PPO resistance (Group 14). Some farmers are now resorting to hand-weeding.

“I challenge anyone to come up with an effective herbicide program that I could place in that field and successfully grow a Roundup Ready or conventional soybean crop – because it’s not possible,” Norsworthy says.

The prolific seed production also makes the weed a threat, and patch management is key if a population is introduced into a field. In February of 2008, Norsworthy established 20,000 glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth seeds in a one square metre circle to represent the surviving seed of a single Palmer amaranth female plant. That fall, Palmer amaranth was located as far as 400 feet downslope, believed to have moved downhill with rainwater. In 2009, it infested 12-to-31 per cent of the total field area. In 2010, infestations reached greater than 95 per cent of the total field area and the crop was abandoned due to the high weed competition.

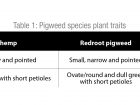

For Canadian farmers who do not yet have Palmer amaranth, scouting will be key in helping to slow the spread if the weed does move North. However, weed identification is difficult at the seedling stage, since it is similar to waterhemp and redroot pigweed. North Dakota State University has a dedicated webpage on Palmer amaranth, with photos and links to other State University sites.

If identified, weed scientists agree that zero tolerance should be the goal, with patch management using tillage, herbicides, and hand weeding as key to helping stop the weed from gaining a foothold in a field. Pesticides alone won’t be sufficient, especially if Roundup Ready crops are grown in tight rotations.

“Diversity, diversity, diversity in your long-term integrated crop and weed management programs will be essential,” Sikkema says.