Features

Diseases

Canola

Evolving blackleg management strategies

Scouting is at the core of disease management.

November 20, 2019 By Bruce Barker

Blackleg causes premature ripening in canola.

Photos courtesy of Gary Peng.

Blackleg causes premature ripening in canola.

Photos courtesy of Gary Peng.

Blackleg just doesn’t go away. With many different and evolving pathotypes, researchers and plant breeders are trying to stay one step ahead of the disease. Research scientist Gary Peng with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Saskatoon has been working on blackleg as one of his disease priorities for many years.

“Even after 10 years there are still questions that we are working on,” says Peng, who summarized what researchers know about the disease at the Manitoba Agronomist Update conference last winter.

Peng says that blackleg behaves differently on the Prairies than other parts of the world. In Canada, our growing season is around 100 days, compared to 200 in Australia and 300 in Europe. As a result, early infection of a canola plant, especially on cotyledons, by the pathogen is critical for disease development, and this early infection has management implications.

In the 1990s before blackleg resistant varieties were developed, blackleg had become a major disease problem in Western Canada with incidence in the 50 to 60 per cent range. After resistance varieties were developed in the early 1990s and with longer crop rotations than today, blackleg incidence dropped to very low levels. But Peng says that starting around 2010, incidence has trended upward and is currently sitting at around 10 to 15 per cent, depending on the year and area.

“The big question is ‘what is causing it to creep up?’ We don’t really know for certain, but we know of some of the possible explanations,” Peng says.

Scouting is important

One possible reason that the reported incidence has trended upward recently is that there is more scouting and formal surveys being conducted, led by the each of the Prairie provinces’ agriculture ministries. Essentially, if you look for something, you’re more likely to find it. But Peng says increased scouting for blackleg is a good thing, as it helps farmers, agronomists and researchers keep track of the disease.

“Of all the management strategies that can be done on the farm, scouting is the most important, because it helps to guide other management strategies,” Peng says. “On the Prairies, we’re still dealing with relatively low incidence, so scouting can help keep track of the disease on individual fields.”

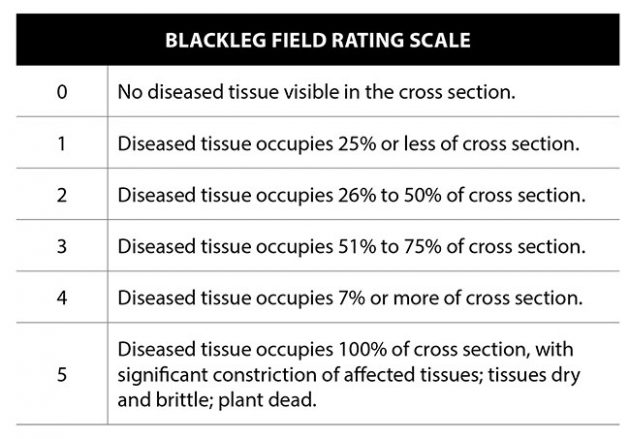

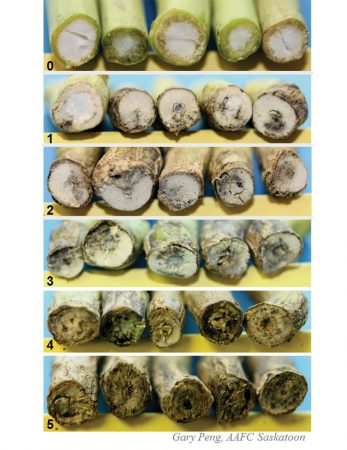

Due to improved variety resistance, the visual symptoms of severe stem canker have become uncommon. Now, the best way to scout for blackleg symptoms is to cut the stem off at the soil surface around the time the crop is swathed or straight combined. Blackening inside the basal stem is now the more common symptom. Peng has developed a pictorial scale for a rating system to help assess the severity of blackleg infection, with a scale from “0” to “5” (see chart, above). With today’s resistant varieties, he says blackleg incidence shouldn’t be higher than 10 per cent, or severity higher than a “1” on the rating scale.

“It needs emphasizing that to know your risk, scouting is the most important thing to do on the farm,” Peng says.

Crop rotation

Crop rotation is another important management practice, and with tighter rotations, may be another possibility as to why blackleg incidence has been trending higher recently. The ascospores and/or pycnidiospores that infect canola reproduce on canola stubble. Blackleg fungus does not survive without canola stubble so a greater than two year break from canola provides more time for canola stubble to decompose.

The two spore types infect canola differently. Ascospores require a 16-hour dew at 20 C to infect canola cotyledons or leaves. Pycnidial spores normally only infect through wounds on canola tissue. For example, flea beetle feeding on cotyledons may provide an opportunity for early season infection, and early season infection is correlated to severe damage. Therefore, blackleg may be considered as monocylic with only one opportunity per growing season to infect canola, and early season wound infection on cotyledons can be an important factor in blackleg development.

Pathogen populations changing

Researcher Randy Kutcher, now with the University of Saskatchewan’s plant sciences department, first looked at the frequency of different pathogen types carrying distinctive Avirulent (Av) genes in 2007. At that time, Av2 and Av6 dominated the populations across the Prairies. Since 2010, researchers have been surveying pathotypes regularly, and by 2017, the Av2 pathotypes had noticeably decreased while Av7 had become one of the dominant pathotypes.

“These surveys help to tell us what the dominant pathotypes are on the Prairies, and that information helps plant breeders develop varieties with corresponding resistant genes,” Peng says. “For example, with the high frequency of Av7 in the pathogen population, breeders may deploy the resistance gene Rlm7 in canola varieties to combat the disease effectively.”

Understanding pathotype incidence, and the corresponding major resistant genes has allowed for the development of a blackleg resistance labeling system. Seed companies can voluntarily label their varieties showing which resistant genes are included in a variety. This information can help guide variety selection if a variety is starting to show higher blackleg incidence and severity – a sign that the Av genes have shifted in the field.

Peng cautions that farmers shouldn’t just rely on variety resistance to manage blackleg. For every resistant gene available to plant breeders, there is a virulent race that can overcome it on the Prairies.

Researchers have made great advancements in understanding and preventing blackleg, but Peng advises the best mode of action is scouting at the farm level for risk assessment. Photo courtesy of Justine Cornelsen.

Understanding quantitative resistance

In an attempt to understand the resistant genes used in western Canadian varieties, plant pathologist Dilantha Fernando at the University of Manitoba collected a large number of canola hybrids/breeding lines and analyzed them to determine resistant gene diversification. Only Rlm1 and Rlm3 resistant genes, especially the latter, were commonly found. These resistant genes are active on Av1 and Av3 genes carried by the blackleg fungus. However, the dominant Av genes in 2017 were Av4, Av6 and Av7.

Peng explains that the reason that blackleg isn’t a greater problem is that another type of resistance called quantitative resistance is helping to suppress the disease. “There is a level of quantitative resistance in the varieties and it has a different mechanism as opposed to major gene resistance.”

Quantitative resistance limits the spread of the blackleg pathogen in the plant, slowing or stopping the disease reaction. AAFC researcher Michelle Hubbard, based in Swift Current, Sask., found that quantitative resistance helps to limit stem canker development and reduces final disease severity. The pathogen spreads more slowly through the petiole and stem, resulting in a lower incidence of disease.

“Quantitative resistance is a valuable addition to major gene resistance, especially in Western Canada where blackleg pressure is relatively lower than that in Australia or Europe. We are working to get a better understanding of how it works and how it can be used in plant breeding,” Peng says.

Fungicide research

Peng has been involved in several research projects looking at the use of fungicides for blackleg control. He first led a group that looked at foliar fungicide application at the two to four leaf stage or at bolting on the susceptible variety Westar. Over the 17 site years, application of a strobilurin fungicide at the early stage resulted in a significant decrease in disease incidence and severity, and a significant increase in yield.

However, splitting the 17 site years into light severity (0.5 rating) and heavier (2.5 rating) showed a different story. Under light blackleg disease severity, foliar application at either stage did not result in any significant differences. Under heavier disease pressure, early fungicide application with pyraclostrobin or azoxystrobin significantly reduced disease incidence and severity, and increased yield.

Another trial was conducted using a blackleg resistant and a moderately resistant variety. While application of a strobilurin at the two to four leaf stage reduced disease incidence and severity, even under heavier disease pressure (rating 1.3 to 2.0), yield was not significantly increased over nontreated control.

“This shows the importance of using a resistant or moderately resistant variety, and when you use one of those varieties, a fungicide application would likely not pay,” Peng says.

Recently, Peng started investigating new fungicide seed treatments. While Helix and Prosper seed fungicides do not prevent blackleg infection on cotyledons, he says a new chemistry is showing good potential. The chemistry appears to be a better insurance policy against blackleg when combined with a resistant variety. Peng’s research supports product registration based on the efficacy data from Western Canada and hopes that a couple of new seed-treatment products will be available very soon.

For all the advancements made in understanding and combating blackleg in Western Canada, Peng says the foundation for managing the disease is scouting at the farm level. “The most important thing you can do is scouting for risk assessment. Crop rotation and variety rotation will follow based on what you find in the field.”