Features

Agronomy

ag150

Diseases

Present

Field crop disease management in Canada part two: Where are we now?

May 11, 2017 By Dr. Bruce Gossen

OUR PRESENT SITUATION

Cropping rotations are getting shorter. When I was a young pathologist working in Saskatchewan, a lot of growers were growing as many as five different crops, even sometimes seven different crops in their rotation. Now crop rotations often only have wheat and canola. At the same time, fields are getting larger. In addition to reduced biodiversity, this means less biological control, and we’re seeing some new and really problematic pathogens.

These new pathogens are long-lived. Many of them have been introduced from other places and are quite invasive; there are no sources of resistance (right now) and fungicides aren’t effective. Our main vehicles for control aren’t working for us on these particular problem diseases, which is why they’re problems.

The case of clubroot

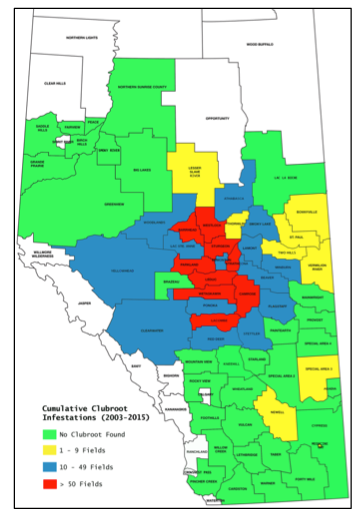

Clubroot on canola is one example. Between 2004 and 2007, there were a few fields found around Edmonton. By 2016, there were more than 2,000 infested fields identified in Alberta.

CLUBROOT MAP COURTESY OF STRELKOV.

CLUBROOT MAP COURTESY OF STRELKOV.

In Alberta, clubroot variety resistance is starting to break down. This is a nightmare for breeders because there are at least nine new pathotypes and right now we don’t have any genes for resistance that can deal with all nine. The plant breeding companies are working very, very hard to identify new sources of resistance, but in the end, we’re going to have to find another approach. Once you’re on this treadmill where you get new resistance and it breaks down quickly, you can come to a sudden stop where there’s no new resistance. We have to get off the treadmill.

The reason why clubroot is such a problem and breakdown of variety resistance is a concern is there are hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of tiny spores per cell in the roots of these clubbed roots. There can be a billion spores on a single plant. That means a lot of disease increase in a very short time.

And it moves quickly: it can move in soil, in wind-borne soil, and even in water, but the main mechanism is infested soil on equipment. If we go into growers’ fields to do surveys, the place we look first is the field entrance, because that’s where the soil from the last field tends to drop off and that’s where the disease starts.

There’s been a lot of talk about sanitation – cleaning equipment. I think that’s ridiculous. Who’s got the time to be cleaning equipment between fields in a wet spring when your equipment is the muddiest? But if you know you’ve got a single place or a few places where there’s clubroot, seed them last to keep the disease where it already is rather than spread it around your farm.

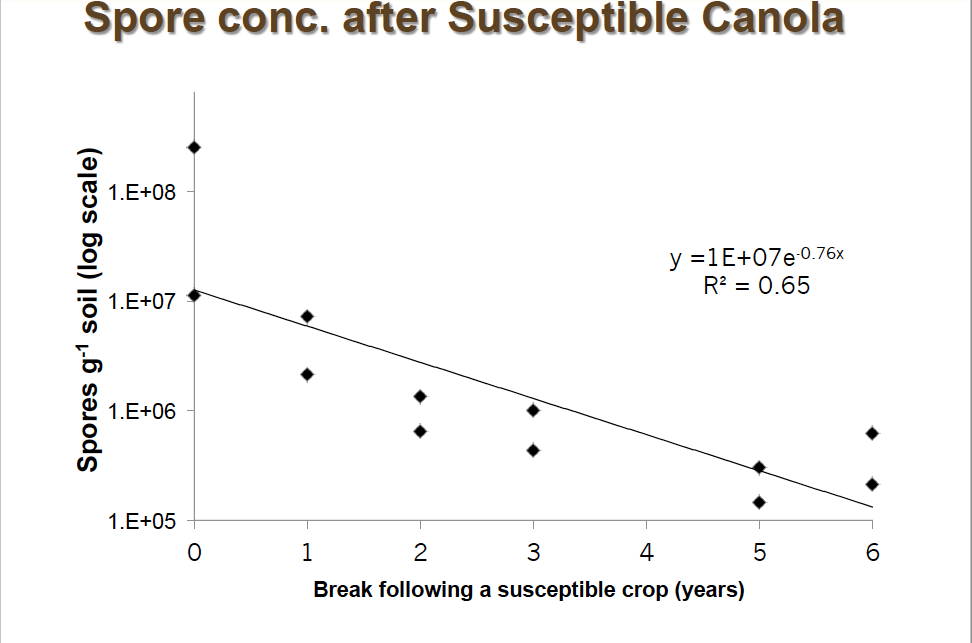

The good news is that it looks like the clubroot pathogen doesn’t live forever in soil. We are seeing that even two to three years out of canola allows the pathogen population to decline substantially. This is where Saskatchewan [and Manitoba] growers are in pretty good shape because you don’t have this disease yet, so you can manage it in a more effective way with crop rotation.

SOURCE: J. DALTON, MSC THESIS, 2016.

The clubroot pathogen doesn’t like alkaline soils. Research found that in warm, acidic soils, there was 100 per cent infection in a very short time. At that same high temperature of 25 C and a pH of 8, we only found 40 per cent infection. This indicates that a few spores in a field with alkaline soils will probably not create a problem. But if you get a huge lump of soil coming off a cultivator as you drive into the field, that’s going to be a source of infection and it’s likely going to be there for a long time.

We’re working with growers right now in Alberta to try and deal with hot spots of infection, mostly of the new pathotypes that are showing up. The first thing is to identify the area that’s infested – that would be mainly by symptoms – and then to treat it with lime to increase the alkalinity of the soil.

In places such as Ontario, where there are custom fumigant applicators, growers can fumigate the soil and kill many of the spores. It’s really costly but if it’s a small area, it might be worth it. Then seed that area down to a grass so that the soil doesn’t move around. Once the pathogen is pretty much gone, then you can go back to production, but you can go back to production only with resistant cultivars because there will still be some spores in the soil and infection will start again if you go back with susceptible material.

Click here to see part three: what the future holds

This article is a summary of the presentation “Management of Field Crop Diseases: Past, Present and Future,” delivered by Dr. Bruce D. Gossen, Saskatoon Research and Development Centre, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, at the Field Crop Disease Summit, Feb 21-22, 2017, in Saskatoon. Click here to download the full presentation.