Features

Agronomy

Insect Pests

Cutworm “outbreaks” lasting longer

If you’ve been noticing more cutworm damage in your fields recently, you may have good reason. Cutworms are cyclical by nature, and the last five to seven years have had cutworms at outbreak levels in some areas of the Prairies. Vincent Hervet with the University of Lethbridge has been studying cutworms as a PhD student, and is working in collaboration with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada on the biological control of cutworms. He says the most recent outbreak has lasted longer than usual. While cutworms aren’t a widespread problem, where they are a problem, they can be a big problem.

“In the past, we’ve seen a three-year type of cycle with the second year having the most cutworms and the third year they are going into decline. The decline is usually associated with weather and natural enemies,” explains Hervet. “We’re not sure why this cycle is lasting longer.”

There are about 1000 cutworm species in Canada but only about 30 species considered pests in the southwest Canadian Prairies. Seven species have caused the majority of cutworm damage in recent years – redbacked cutworm, darksided cutworm, army cutworm, dingy cutworm, pale western cutworm, glassy cutworm and bristly cutworm. Hervet says most of these cutworms were not particularly important pests a few decades ago.

“Recent weather changes and/or changes in agronomic practices and types of insecticides used may have induced this species switch. I’ve noticed the previous cutworm pests of economic importance, such as yellow-headed cutworm and wheat head armyworm, are still present in high numbers in the environment, and may become a problem again if their environment evolves to become more favourable for them,” says Hervet.

Cutworms are not actually true worms, but caterpillars. They are the larvae of some moth species. Hervet says growers and agronomists should learn to properly identify the cutworms so they can properly monitor the pests and assess whether they should spray for them. Unnecessary spraying can also kill beneficial insects that help keep cutworms under control.

Hervet says it is important to identify the species of a particular cutworm because different species have different biology and behaviour. Some of the species will clip stems more than others. Others develop faster and require vigilant scouting. Size matters too, as some species are more of a threat at a certain size, while others of the same size may not be a threat.

Knowing when a cutworm larvae is fully developed will also help guide the spray decision, as fully developed larvae will soon stop feeding and may not need insecticidal control. The different species will also determine how likely it is for an insecticide treatment to work. Subterranean species, for example, are harder to kill.

Cutworm larvae have a head capsule (hard, noticeable head), and a segmented body with eight pairs of short legs: three pairs of legs (“true legs”) on the three segments following the head, four pairs of legs on the middle of the body (“prolegs” or “false legs”), and a last pair of prolegs at the very rear of the body. During their development, cutworms grow from a length of two to three mm as neonates and reach a length of two to five cm (depending on the species) when fully grown.

Life cycle

Adult cutworm moths fly, mate and lay eggs from the end of summer into the fall. A female moth can lay a few hundred eggs in the soil or on host plants. Army, dingy and glassy cutworm eggs hatch and the larvae start feeding in the fall and overwinter as larvae. Eggs of redbacked, darksided, pale western and bristly cutworm overwinter and hatch in the spring. Cutworm larvae appear in the spring from mid-April to mid-May in warmer areas of the field such as hilltops, south facing slopes and areas of lighter soil. Unfortunately, this also coincides with crop emergence and early development, making crops susceptible to cutworm attack.

The larvae usually molt six times, growing bigger each time, until they bury deeper into the soil to pupate. They emerge as moths in summer, completing one generation per year.

Cutworm larvae usually feed at night and hide under plant debris or below the soil surface during the day. Hervet says different cutworm species have preferred plants but do not necessarily restrict their diet to these plants. Glassy and pale western cutworms prefer cereals. Redbacked and darksided cutworms are mainly a problem in small grains, broadleaf crops such as beet, canola, mustard and flax. The dingy cutworm prefers legumes (e.g., alfalfa, pea, clover), but is sometimes also a problem in various other crops. The army cutworm is a pest of most crops in the Prairie provinces.

Damage is evident with cut or partly eaten stems, cut leaves and partly eaten leaf blades. Underground damage shows up with wilted, dry aboveground leaves and damaged stem near the soil surface. When the crop is germinating, cutworm larvae may eat the emerging leaf, which can be confused with poor germination. The field may remain bare in patches.

Take control

Hervet says if cutworm damage is observed, growers and agronomists should look for cutworm larvae, and positively identify them. There may be multiple cutworm species in one field. He lists several situations in which growers may not need to use insecticidal control: the plants are big enough to compensate for the damage; the plants left are not too sparse and the plants left will grow bigger and produce more shoots to partly compensate the loss; the cutworms found are fully grown so will soon stop feeding; dead cutworms are present, which may indicate pathogens or other natural enemies are decimating the population; the cutworms are mainly subterranean species, thus control will be more difficult and expensive; there is an extended period during which the soil is very moist, thus cutworms cannot go underground to hide from their natural enemies that can control them.

“The main approach is to know what is doing the damage, and when it makes sense to kill them with insecticides,” says Hervet.

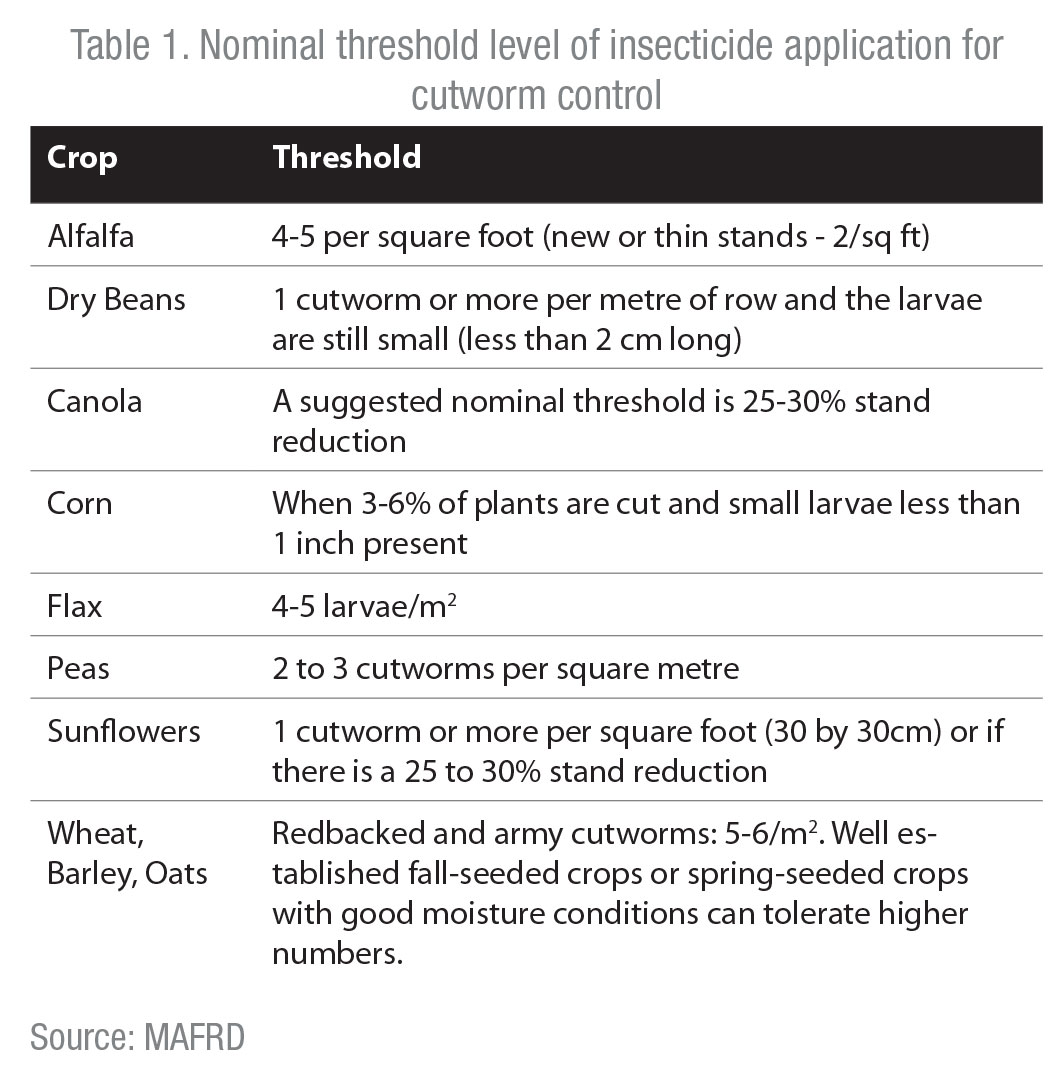

Nominal thresholds for insecticide application have been developed based on experience (see Table 1). When possible, spot spraying of patches will help to preserve natural enemies of cutworms.

Help out the natural enemies

Pathogens, predators and parasitoids are three main categories of natural enemies of cutworms. Pathogens include viruses, bacteria and fungi, along with some nematodes and protozoa. Predators include ground beetles and arachnids (spiders). Parasitoids include certain wasp and fly species.

While many of these predators and parasitoids are difficult for growers and agronomists to identify in the field, they do play an important role in bringing cutworm cycles back below economic thresholds. Hervet says evidence of parasitization can be found by looking for parasitoid wasp pupal masses on plants, parasitoid “maggots” inside cutworm larvae, and by looking for dead caterpillars.

“As long as the cutworm populations are below threshold, the message is to hold off on spraying. These beneficial insects are very tiny and get decimated by insecticides.” explains Hervet.

For now, the technology doesn’t exist to use these natural enemies in a biological control program. Rather, Hervet says growers should aim to provide the natural enemies a helping hand. Insecticides should only be used as a last resort to save the crop. Avoiding cultivation and soil disturbance helps preserve a good environment for natural enemies. Maintaining some biodiversity in a field, like having a few weeds present, is a good thing. Flowering weeds are important for keeping parasitoids alive, says Hervet.

“When parasitoid adults emerge from their pupa, most species need to feed within the next few hours or day, otherwise they die. Many parasitoid species will not even be able to mate or parasitize unless they have previously fed. Flowers scattered throughout the field provide a food source (nectar) that will keep these parasitoids alive long enough to allow them to mate and parasitize pests,” explains Hervet.

The idea of “beetle banks” in fields may be a future solution. These “banks” are two to five metre wide strips of permanent grass and flowering plants seeded within the field to preserve populations of predators, parasitoids and pollinators in the field. Hervet says beetle banks have been successfully used in the UK where the preservation of natural enemies was successful with a corresponding decrease in pest populations. They haven’t been tested in North America.

December 3, 2014 By Bruce Barker

Damaged canola stem showing cutworm feeding. Cutworms are cyclical by nature

Damaged canola stem showing cutworm feeding. Cutworms are cyclical by nature