Features

Agronomy

Tillage

Conservation tillage through the decades

It’s amazing to see how far western Canadian agriculture has come. Forty-five years ago, conservation tillage was unknown, save for a few forward-thinking research scientists and concerned farmers. In 1970, a world wheat glut had wheat prices low and federal agricultural initiatives produced Lower Inventories for Tomorrow (LIFT) where farmers were paid to keep land out of production. The result was a dramatic increase in summerfallow, with some land not seeing a grain crop for several years. Salinity was on the rise and dust storms were brewing.

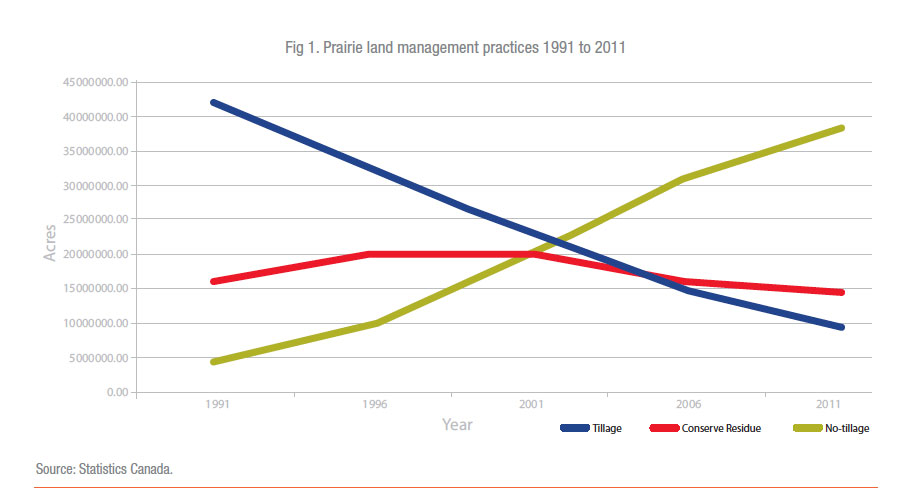

Fast forward to 2011 when the last Statistics Canada Census found 62 per cent of land was seeded with no-till and an additional 24 per cent seeded with a low disturbance system that left most of the crop residue on the soil surface. The time between then and now was truly transformative and revolutionary, spawning new crops, machinery innovation and a more sustainable agriculture. (See Fig. 1.)

Early pioneers

Dust storms weren’t new to the Prairies in the 1970s and 1980s but old tillage habits die hard. Following the Dirty Thirties, research scientists at Agriculture Canada Experimental Stations across Western Canada, as well as the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Act (PFRA), focused on keeping crop residue on the soil surface during summerfallow years.

According to the book Landscapes Transformed, The History of Conservation Tillage and Direct Seeding*, published by Knowledge Impact Society at the University of Saskatchewan (U of S), the earliest concept of reduced tillage seeding, where farmers seeded directly into standing stubble, was developed by R.A. Johnson, a Saskatchewan farmer, who is credited with developing the one-way discer seeder in the 1940s. Many machinery companies, including Cockshutt, produced the seeder, which allowed farmers to direct seed without pre-seed tillage, albeit with high soil disturbance. The development of herbicides to control weeds also helped farmers reduce tillage after the Second World War.

Early research on no-tillage highlights the concern some pioneering scientists had regarding the detrimental effects of tillage on soil degradation. Edward H. Fowler published The Plowman’s Folly in 1943 and made the case to get rid of the plow, stating: “No one has ever advanced a scientific reason for plowing.”

The first commercial no-till drill was introduced in 1967 by Allis-Chalmers, although it wasn’t suited to small grain crops. Machinery limitations were a major barrier for these early pioneers.

|

Agriculture Canada researchers continued to look into ways to reduce tillage, and in the 1960s, C.H. Anderson looked at low-disturbance direct seeding, reporting in 1971 that “…direct seeding with hoe and double disc press drills provided equal yields to that with pre-seeding tillage from 1966-1970 at Swift Current [Sask.].” At that time, however, Anderson pointed out that direct seeding was more of a scientific exercise: “Economics was not considered; we wished only to ascertain whether cultivation had any beneficial effect other than for weed control.”

Other researchers were doing low-disturbance direct seeding in the late 1960s and early 1970s as well, including Agriculture Canada researchers Wayne Lindwall at Lethbridge, Alta. and Ken Bowren at Melfort, Sask. University researchers included Elmer Stobbe at the University of Manitoba and Brian Fowler at the U of S.

Explosive growth

Many factors collided in the 1970s and 1980s to drive the no-till movement. Don Rennie, a former dean with the U of S’s college of agriculture, joined the university in the early 1970s and started to promote the message that summerfallowing was not sustainable and was actually destroying cropland.

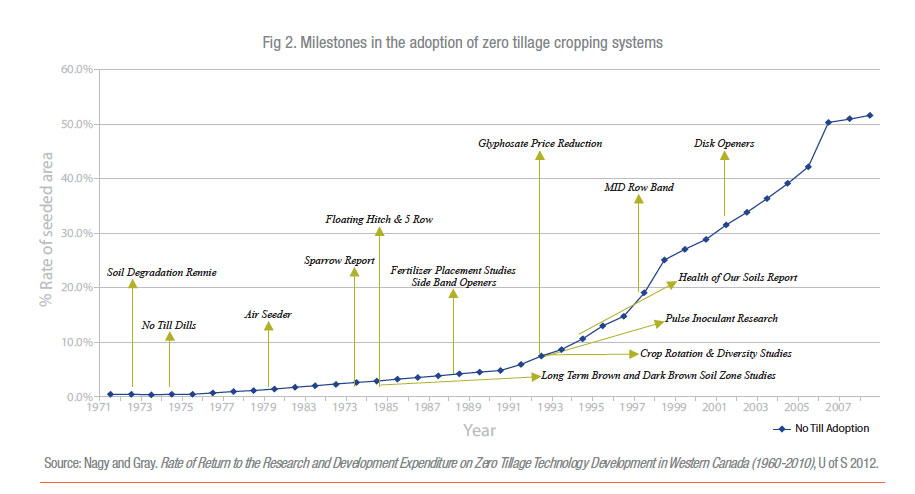

While the message was controversial at the time, it has been proven many times over. Still, farmers had few practical or economic ways to implement direct seeding or no-till. Machinery was a major limiting factor, as was weed control. The Haybuster drill was one of the early no-till drills, but its limitations of seeding efficiency and residue penetration with discs limited its use. (See Fig. 2.)

|

Air seeding technology gradually started to develop in the late 1970s and early 1980s. One of the earlier air seeders, developed by Ross and Davies of Antler, Sask., was patented in 1975 and went into commercial production in 1979 as the Prasco air seeder. These early air seeders, though, were primarily used for banding fertilizer – a concept championed by John Harapiak of Western Co-operative Fertilizers Ltd., who subsequently did research on seed and fertilizer placement in direct seeding. The air seeders were simply cultivators with an air delivery system, not necessarily designed for seeding crops with poor depth control across the toolbar.

In 1984, Canadian Senator Herb Sparrow delivered the Soils at Risk report on soil erosion and ways to minimize it, including investment in research, farmer education, government policy, and the creation of national and provincial councils to promote better soil conservation. It became one of the best-circulated Senate reports. Farmers were ready for the message, and the droughts of the mid-1980s served to emphasize the concept of soil and moisture conservation.

Information from Alberta Agriculture indicates the 1980s were a time of innovation for machinery. Friggstad Ltd. began producing air seeders using Wieste components from Germany. Flexi-coil produced a modified Australian seeder from Fusion Engineering called the Air Flow seeder in 1981. Morris sold the Australian Napier Grassland seeder; Bourgault utilized the Bechard seeding system in their seeder. Others producing air seeders included Wil-Rich, Leons, Concord, Great Plains, Case IH, C.C.I.L. and John Deere.

In the mid-1980s, floating hitch and five row toolbars were developed, allowing better depth control for seed and fertilizer placement. Openers were generally cultivator sweeps or spoons where seed and fertilizer were scattered together. These openers limited the amount of fertilizer that could be applied with the seed, and still resulted in large soil disturbance during seeding. At that time, wide sweeps provided pre-seed weed control in the absence of effective and affordable herbicide control.

Sideband openers were eventually developed, allowing farmers to place seed and fertilizer separately. These openers were one of the key factors that allowed farmers to move to a one pass seeding system.

Still, farmers struggled to control weeds economically before seeding. Roundup was introduced in 1974 but wasn’t economical for broad spectrum weed control until 1983 when Monsanto started to reduce the price in anticipation of the patent on glyphosate expiring. The development of herbicide-tolerant crops gave farmers even greater choice and ease of weed control in no-till.

From 1971 to 1993, no-till seeded acres was only approximately eight per cent of seeded acres. With the price of glyphosate dropping as competition entered the marketplace, the tipping point was reached for farmers looking to enter no-till. From 1993 to 2011, no-till grew to 62 per cent of seeded acres.

In the intervening years, machinery innovation continued, with Seed Hawk, SeedMaster and ConservaPak developing independent, ground following opener systems. Notably, these systems were developed by farmers like Pat Beaujot, Norbert Beaujot and Jim Halford, who were all looking for a better way to no-till seed. Mid-row band technology was developed, and disc openers were refined. Today, no-till equipment is reliable and falls mainly into independent openers systems or disc drill systems.

The perfect storm

Many factors, including machinery, herbicides, cost of production and increased cropping choices with no-till, provided the foundation for the explosion in no-till, but researchers and farmer organizations certainly played a key role. The Manitoba-North Dakota Zero-Till Farmers Association, the Alberta Conservation Tillage Society (eventually Alberta Reduced Tillage LINKAGES) and the Saskatchewan Soil Conservation Association took up the cause. The efforts of these organizations, through extension, field demonstrations and annual conferences, helped drive technology transfer. It wasn’t uncommon for field demonstrations to draw hundreds of farmers and annual conferences to pull in 500 or more farmers.

Research scientists were also heavily involved in low disturbance direct seeding research, and spent much time in the 1980s and 1990s conducting research and technology transfer. Significant trials were initiated by Wayne Lindwall at Lethbridge, Stewart Brandt at Scott, Sask., Ben Dyck and Sylvio Tessier at Swift Current, and Guy Lafond at Indian Head, Sask. The Prairie Agricultural Machinery Institute tested much of the new equipment throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Many more trials were conducted off-site on farmers’ fields. Since then, many more scientists have conducted research into conservation tillage and have gained a better understanding in nutrient management, weed control, crop diversification and rotation, and disease management.

A U of S study (Nagy + Gray) published in 2012, Rate of Return to the Research and Development Expenditure on Zero Tillage Technology Development in Western Canada (1960-2010), stated: “A return of $52 dollars for every dollar invested in zero tillage research by public, NGOs and private sector was estimated. Approximately, 50 per cent of the $3.4 billion net benefit of the research was captured directly by farmers in terms of fuel, labour, machinery and other input cost reductions.”

Since the 2011 Census, no-till has likely suffered some with the above-normal rainfall and flooding in some parts of the Prairies. For most of the last 100 years, Prairie farmers have been trying to conserve moisture, while over the last 10 years there has been too much in some areas. Old cultivators have been dusted off and used to dry out soils. New vertical tillage equipment has been promoted as a way to dry out the soil as well.

So is tillage making a big comeback? Given the many sustainable benefits of no-till, the answer is likely no, except for localized areas were environmental conditions dictate some tillage. But only time will tell what the next 40 years will bring.

*Landscapes Transformed is a must-read for those interested in the history of Conservation Tillage in Western Canada. Significant parts of this article are based on this book, with permission.

August 7, 2015 By Bruce Barker