Features

Agronomy

Canola

Diseases

Combatting clubroot in Ontario

Clubroot project yields promising management strategies.

May 8, 2020 By Julienne Isaacs

Grass cover crops work best if clubroot-susceptible weeds – such as shepherd’s purse, peppergrass, yellow rocket and

volunteer canola (pictured) – are controlled in a field. Photo courtesy of Mary Ruth McDonald.

Grass cover crops work best if clubroot-susceptible weeds – such as shepherd’s purse, peppergrass, yellow rocket and

volunteer canola (pictured) – are controlled in a field. Photo courtesy of Mary Ruth McDonald. A comprehensive Canadian clubroot project that aims to help canola growers manage the disease is yielding hopeful results.

Mary Ruth McDonald is research program director of plant production systems at the University of Guelph and leads the Ontario research group investigating clubroot management tactics.

Clubroot was confirmed in Ontario canola only as recently as 2016, but has been present in Brassica vegetable crops in southern Ontario since at least the 1960s, says Meghan Moran, canola and edible bean specialist for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA).

“It’s possible it’s been in canola for a long time,” Moran says.

Clubroot is a soilborne disease caused by the organism Plasmodiophora brassicae that leads to gall-like growths on the root systems of cruciferous crops like canola. Galls eventually kill their host plant, and when they decay they leave behind millions of resting spores – so named because they can live for up to 20 years in the soil.

In extreme cases – when resting spore counts are high, and infection starts early – clubroot can cause yield losses of up to 100 per cent.

McDonald’s project is currently funded by a Canadian Agricultural Partnership grant that began in April 2018 and will run until 2023. She works closely with Stephen Strelkov and Sheau-Fang Hwang at the University of Alberta, as well as Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada researchers Bruce Gossen and Gary Peng in Saskatoon.

A constellation of projects is underway across Canada, McDonald says, but the research community is highly collaborative.

“The overall objective of all of this work is based on something that the Canola Council of Canada had presented as a challenge years ago: how can growers grow canola in the presence of clubroot?” she says.

Grass cover crops

McDonald says one promising research area has focused on the use of grass cover crops to control the spread of clubroot in a field.

It’s believed that clubroot is chiefly transported into fields on dirt clods carried by heavy equipment.

“Years ago, Steve Strelkov’s group showed that in Alberta the highest concentrations of clubroot are close to the field entrance, because that’s where the clumps of soil would fall off. A small amount would get started there, and the clubroot would move out into the rest of the field,” McDonald says.

Grass crops like ryegrass are not hosts for clubroot and can help limit the number of resting spores in a field. Research has shown that root exudates from grassy plants stimulate clubroot spores to germinate, but as they cannot form galls and reproduce in grass roots, the overall amount of resting spores diminishes over time, McDonald explains.

Moran says that while western Canadian producers have adopted this strategy, grassing one or two acres at field entrances so they can stop tractors on the way into a field and kick clods off the machines, the practice is less common in Ontario.

Data from field trials conducted by McDonald’s and Gossen’s PhD student Afsaneh Sedaghatkish shows grasses can reduce resting spores by 60 to 78 per cent in only eight weeks.

“Having them in a field for a growing season or more can be even more effective,” McDonald says. “But if the spore counts at the start are over a million per gram, even a 78 per cent reduction can leave enough resting spores to cause high levels of clubroot on susceptible canola.”

In greenhouse and field trials in Ontario, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, McDonald’s group has compared the impact of various grass cultivars on resting spore numbers. So far, smooth bromegrass is a standout, as well as ryegrass cultivar Fiesta, she says, but there are “no grasses to avoid” – in other words, the principle is sound regardless of the cultivar.

“It’s always a good idea to grass the field entrance. We can give some direction about which cultivars might be better, and we’re hoping to look at some more crops and cultivars to make better recommendations in the future,” she says.

She adds that the grass cover crops work best if clubroot-susceptible weeds – such as shepherd’s purse, peppergrass, yellow rocket and volunteer canola – are controlled in the field.

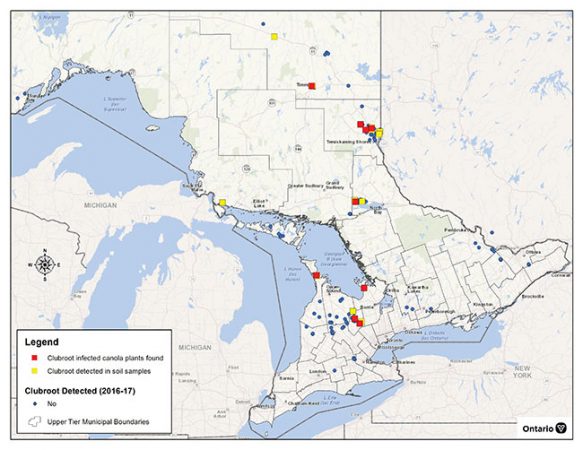

OMAFRA survey data shows that clubroot is widespread in Ontario. Image courtesy of Meghan Moran.

Other management approaches

McDonald has just begun a greenhouse trial at Guelph that will look at the influence of rotation crops on reducing the number of resting spores in an infected area.

Experimental rotations include winter wheat, field peas and barley.

“Our first run of that trial has shown that one cultivar of spring wheat, and a barley cultivar, did reduce the number of resting spores, compared with bare soil,” she says.

Many canola producers rotate with wheat anyway, McDonald says, but the trial might help producers select cultivars based on their ability to directly influence resting spore counts.

In another greenhouse trial at Guelph, McDonald’s group is looking at a combined approach of adding lime to the soil to raise its pH while also using a grass cover crop.

Adding lime to affected fields is a longstanding tactic of Brassica vegetable growers in Ontario, but the practice hasn’t been widely tested in canola. This past year, McDonald’s collaborators began field trials across Western Canada to test the principle.

“Ontario canola growers haven’t yet used lime in combination with grass cover crops, but producers are more and more interested in these additional tools for managing clubroot,” she says. “We think the combination of approaches will be more effective than the use of one strategy alone.”

In a third project, McDonald’s group is looking at the question of how soon after germination Brassica weeds should be terminated in clubroot fields to prevent the increase of resting spores. The results so far are concerning.

“You need to kill those plants after only three or four weeks,” she says. “We have results that show if you spray glyphosate five weeks after seeding, there’s already enough pathogen in the root that it’s multiplied, and once it gets to a certain stage of multiplication, the resting spores will mature and the spores will be released into the soil.”

This underscores the importance of scouting early and often, McDonald says, so weeds can be controlled before they do further damage.

Pathotyping and disease spread

McDonald’s team, in collaboration with Moran and other OMAFRA researchers, have conducted some pathotyping in Ontario fields to attempt to characterize the pathotypes or strains of the disease.

Clubroot-resistant canola varieties are available, but most of these rely on limited resistance mechanisms, meaning virulent pathotypes can overcome that resistance relatively quickly if they’re planted too often.

Clubroot is already widespread in Ontario. Pathotypes 2 and 5 have been identified; pathotype 2 was more common, McDonald says. In summer 2019 the team also discovered pathotype 3X, a new, virulent pathotype that is common in Alberta but apparently new to Ontario. This pathotype can quickly overcome the first generation of resistance, she says.

Second generation resistance – which combines or “stacks” multiple resistance genes – are in seed companies’ pipelines. But McDonald says producers can’t afford to wait for better varieties.

“The seed companies won’t be able to keep up with the development of new pathotypes,” she says.

But Moran adds that clubroot presents differently in Ontario than in Western Canada. Ontario canola producers typically use three- or four-year rotations, and this helps mitigate disease pressure, although it might also “mask” clubroot in a field so the disease is harder to pick up on.

“If you have a four-year rotation you might not notice it as much,” she says. “For some growers, we’ve detected the disease on their farms but they haven’t seen symptoms.”

This simply means producers need to be more vigilant about scouting, she adds. “If they’re scouting, it may not be the fourth canola crop they lose to clubroot before they’re aware they have a problem,” she says. “They’re hopefully more likely to find it when it’s still confined to the field entrances.”

For now, first-generation resistance is still useful in Ontario. It could break down with high clubroot pressure, but Moran says the disease is still in its early stages, and attention to biosecurity tactics will go a long way toward disease prevention and management.

Any producers who suspect they may have clubroot in a field are encouraged to send soil samples to Moran at the Stratford office of OMAFRA, 63 Lorne Avenue E., Suite 2B, N5A 6S4.