Features

Agronomy

Canola

No blackleg, No problem.

Since the early 1990s, blackleg resistant canola varieties have been available in Western Canada, and have helped to prevent yield losses caused by the main races of the pathogen, Leptosphaeria maculans. But the disease is on the rise due to a shift in the races of the pathogen that has resulted in the loss of resistance in some canola varieties in some fields.

September 25, 2018 By Bruce Barker

Since the early 1990s

Since the early 1990s“If you are in a tight rotation of canola-wheat, then you should be monitoring your fields over time to see if the disease is becoming worse,” says Justine Cornelsen, agronomist with the Canola Council of Canada.

In 2017, the Canadian Plant Disease Survey found that the occurrence of blackleg is wide spread across the Prairies, although at low levels of severity. In Alberta, blackleg was present on 82 per cent of fields surveyed, but at a severity of 0.26, indicating that infection rate and severity remains low overall.

In Saskatchewan, blackleg was present in 73 per cent of fields surveyed with an average severity of 0.2. Manitoba results found blackleg in 70 per cent of fields surveyed at severity ratings of two or less.

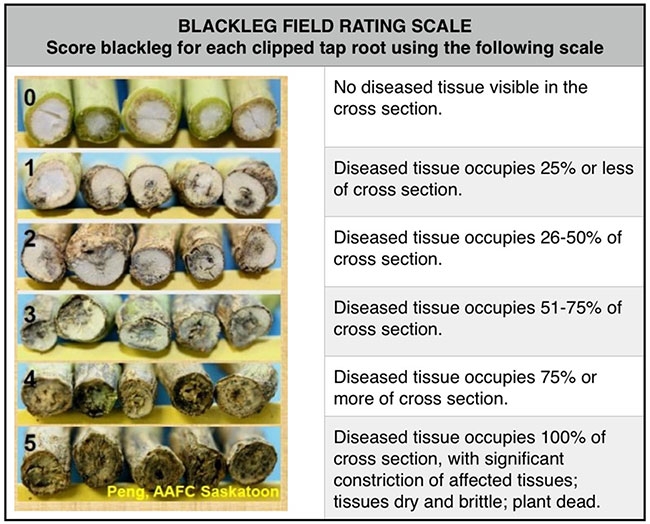

Research scientist Gary Peng with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Saskatoon developed a Blackleg Field Rating Scale to guide agronomists and canola growers on assessing blackleg severity. It can be found at the Canola Council of Canada’s (blackleg.ca). The scale runs from zero, with no disease, to five, where the disease has completely overtaken the stems.

To assess severity, scout for the disease at swathing or straight cut combining by pulling at least 50 plants while walking in a w-pattern. Cut the stem at the base and look for blackened tissue inside the crown of the stem. Compare the stems to Peng’s field rating scale to estimate severity. Cornelsen says that yield impacts will start to be seen around 1.5 to 2 on the rating scale.

“You probably won’t see the disease uniformly across the field as the pathogen usually occurs in patches,” Cornelsen says.

During the winter of 2016-2017, the Western Canada Canola/Rapeseed Recommending Committee (WCC/RRC) voted in favour of the voluntary use of R-gene labels for the Canadian canola industry, as proposed by the Blackleg Steering Group. These labels are voluntary for seed companies, and some began using them in 2018.

Up to 10 new blackleg labels will be used, which correspond to the major resistant genes. They will use letters A, B, C, D, E₁, E₂, F, G, H, X to identify the major resistance genes present.

Resistance grouping

- Resistance A = Rlm1 or LepR3

- Resistance B = Rlm2

- Resistance C = Rlm3

- Resistance D = LepR1

- Resistance E1 = Rlm4

- Resistance E2= Rlm7

- Resistance F = Rlm9

- Resistance G = RlmS

- Resistance H = LepR2

- X = unknown

No M, R or S group to avoid confusion with R/MR/MS/S

For example, if a variety was rated R (BC) this would mean it is rated Resistant with the variety containing the resistant genes Rlm2 and Rlm3. Another variety might be rated R (CX) meaning it is Resistant with the major genes Rlm3 and an unidentified major resistant gene conferring the resistance to blackleg. For growers, the new labeling system will help decide how to rotate varieties to help manage blackleg.

For growers in tight rotations, if blackleg severity and incidence start to build up over time, then rotating to a different resistant gene would be warranted. Seeing low severity across the field but with many plants infected, Cornelsen says that’s an indicator that the major gene is not matching the predominant blackleg race and the variety is now relying on quantitative resistance to hold back the disease.

“The decision to rotate to a different resistance gene really comes back to seeing an increase in disease severity and incidence overtime and how much yield the producer is willing to lose because of it.”

Cornelsen says that if growers have a diverse rotation and are not seeing blackleg in their fields becoming progressively worse, then there is no need to rotate genes. “You might be rotating to a resistant gene that isn’t as good as the one you are using now.”