Features

Agronomy

Canola

Researchers develop new yield loss model to estimate impacts of blackleg disease

Several efforts are underway to develop new tools and management strategies for blackleg disease in canola. Severe epidemics of blackleg can result in significant yield losses. Researchers have developed a new blackleg yield loss model for canola and an associated set of guidelines and recommendations for farmers and industry to help understand the economic impacts of this significant disease.

November 10, 2017 By Donna Fleury

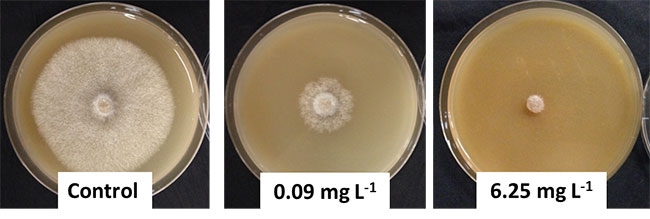

Examples of cultures of the L. maculans fungus grown on medium amended with different rates of pyraclostrobin. new tools and management strategies for blackleg disease in canola

Examples of cultures of the L. maculans fungus grown on medium amended with different rates of pyraclostrobin. new tools and management strategies for blackleg disease in canolaA baseline assessment of potential fungicide sensitivity and resistance has also been established to ensure the sustainability of fungicide approaches to blackleg management.

“In our study we conducted field experiments over three years (from 2013 to 2015) to try and determine the relationship between blackleg severity and how that translates into actual yield losses,” says Stephen Strelkov, professor in the department of agricultural, food and nutritional science at the University of Alberta. “In the field experiments, we grew several canola cultivars to determine the relationship between blackleg disease severity and yield in a susceptible cultivar and in moderately resistant to resistant canola hybrids.”

The canola varieties were seeded into infested stubble that had been inoculated with the blackleg pathogen Leptosphaeria maculans and then compared the differences in disease severity. Plants were rated for disease severity using the blackleg disease rating scale of 0 to 5. Seed yield, pod number and other related factors were measured and analyzed. From the results, researchers were able to explore the relationship between blackleg disease severity and the impact on yield.

“Across all canola varieties, regression analysis showed a straight-forward linear relationship between disease severity and pod number and seed yield loss,” Strelkov explains. “As blackleg severity increased, the pod number and seed yield decreased linearly. We found that for each unit increase in disease severity from 0 to 5, the seed yield declined by about 17 per cent. We also found that blackleg severity was lower, and seed yield was 120 to 128 per cent greater, in the moderately resistant to resistant hybrids compared with the susceptible cultivar.”

The study results formed the basis for the development of the blackleg yield loss model, that, together with the annual canola disease incidence and severity survey data, can help inform growers, agronomists and industry on realistic losses to blackleg in a given area or across industry in a particular year. This project is consistent with results reported from previous work conducted in the U.K. and also in Eastern Canada, but under western Canadian conditions. The research project wrapped up in 2017, and the yield loss model and recommendations have been provided to the Canola Council of Canada and industry.

“Although the research trials were completed in Alberta, the model is applicable across Western Canada,” Strelkov says. “The model can now be used to provide an indication of yield losses in canola that can be attributed to blackleg in individual fields or on a local or even regional scale. This blackleg yield loss model and associated recommendations will also help producers make informed crop management decisions and estimate economic disease impacts.”

Clint Jurke, agronomy director with the Canola Council of Canada has used the new yield loss model. “The information has been very useful to help industry understand how economically important blackleg is. Although blackleg wasn’t a real concern 10 or 15 years ago, today has become a more serious disease for canola growers.” Jurke emphasizes that growers need to be thinking about how the disease levels and yield loss numbers are increasing, and shouldn’t assume they are not losing yield to blackleg infection – the surveys and yield loss model are indicating otherwise.

“We have been using this yield loss model to estimate the amount of loss across the entire canola growing belt and to quantify how economically important blackleg is,” Jurke adds. “We use the annual canola disease numbers to estimate the amount of blackleg infection there is across the canola growing area, then apply the model to estimate how many tonnes of canola we lose each year for blackleg. It is actually a pretty good tool to have for us to be able to understand the importance of blackleg on canola production for farmers and the canola industry. It also supports the need to continue investment into the development of new solutions for dealing with this disease.”

Evaluating potential fungicide sensitivity

Researchers included a second component in the project that set out to evaluate the sensitivity of a representative collection of L. maculans isolates from Western Canada to the fungicide pyraclostrobin. “Some fungicides are considered to be more at risk for the development of fungicide insensitivity, and the fungicide pyraclostrobin is one of those,” Strelkov explains. “Similar to herbicide resistance, some fungi can become less sensitive after repeated exposure to a fungicide.”

Researchers conducted a baseline assessment of pyraclostrobin insensitivity using two different testing methods – agar plate and microtiter plate assays – on a collection of 117 isolates obtained in 2011 from fields across Alberta. The tests provided an assessment of the impact on isolate growth at different levels of pyraclostrobin. The Headline fungicide, which was registered in Canada in 2010, was applied at different frequencies and at different growth stages to create a gradient of disease levels to measure the impact of blackleg on canola and seed yield.

“The good news is we did not detect any pyraclostrobin insensitivity in the baseline tests or in field experiments so far,” Strelkov says. “In field experiments, results show pyraclostrobin fungicide reduced disease severity in all site years, and increased yield. These results also show that the reduction of blackleg in canola crops substantially improves yields. Gaining knowledge of the occurrence of potential fungicide resistance in L. maculans populations on the prairies will help determine the risk of a control failure in the future.”

Researchers now have a foundation for understanding the impact and risk for fungicide insensitivity, however Strelkov cautions that baseline results were from isolates collected in 2011. Therefore, it may be worthwhile to monitor again in the future to see if there have been any shifts in isolates or population insensitivity since that time.

The study showed that this fungicide could be an effective and sustainable blackleg management tool for canola growers, as long as fungicide stewardship is practiced and included as a component of an integrated pest management plan. Farmers are reminded to be cautious in terms of applying fungicides, and to use them along with other best practices including resistant cultivars, and other disease management strategies such as crop rotation, residue management, and the application of seed and foliar fungicides to mitigate yield losses caused by blackleg.