Features

Cereals

Barley designed for Eastern Canada

Developing feed, malt and food varieties adapted to Ontario, Quebec and the Maritimes.

May 16, 2023 By Carolyn King

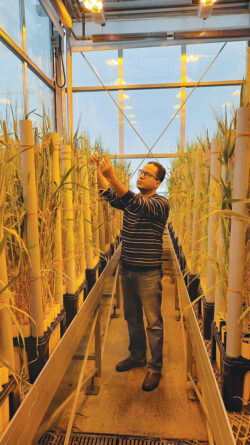

Khanal takes field notes on his barley lines.

All photos courtesy of Raja Khanal/AAFC.

Khanal takes field notes on his barley lines.

All photos courtesy of Raja Khanal/AAFC. Barley breeding has gone high tech – and high speed.

“These days, in the Ottawa barley-breeding program, we are using cutting-edge technologies such as speed breeding and genomic selection to develop new barley varieties for eastern Canadian growers,” says Raja Khanal, the research scientist who leads this Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) breeding program.

The program is releasing a stream of high-yielding barley varieties suited to eastern growing conditions and a range of end-uses, from livestock feed to specialty markets.

Faster varietal development

Speed breeding is a way to shorten the time needed to grow successive generations of plants. Just after Khanal started with AAFC in 2017, he saw an article in Nature about this technique. He was intrigued by its exciting potential and decided to try it in his breeding program.

“Speed breeding uses an artificial environment with higher temperatures and enhanced light duration to create a longer day length to speed up the crop’s breeding cycle. The technique involves growing plants under near-continuous light – for example, 22 hours of light and only 2 hours of dark. That allows the plants to photosynthesize for a longer time, resulting in faster growth,” he explains. “With this technique, we’ll produce almost four generations of barley plants in the greenhouse in one year, instead of one generation per year in the field. That will help us to reduce the breeding cycle, making our program almost two to three years faster than a conventional breeding program.”

In a conventional program, developing a new variety can take 10 or more years. With speed breeding, it might take seven or eight years. This faster approach, especially when coupled with advanced breeding tools like genomic selection, could make a big difference to growers and end-users on the lookout for improvements in key barley traits.

Khanal’s team uses speed breeding for the early generation increases in the greenhouse. “Then, after five generations, the lines go to the single-row field nursery at Ottawa; normally, I have 10,000 single-row plots. Then I make my preliminary selections out of that.”

Those selections are grown in mini-plots at Ottawa. Then, the more promising lines go to preliminary yield trials at Ottawa and Charlottetown. From there, the best-performing lines go to advanced yield trials at multiple sites in Prince Edward Island, Quebec and Ontario, as well as one site in Manitoba.

The program develops varieties suited to the different growing regions within Eastern Canada, and is the only barley breeding program to develop varieties specifically for the Maritimes. Most of the barley varieties grown in the Maritimes are from the Ottawa program.

“It is really important to have a diversity of environments in the breeding program. It leverages geography to figure out how the plant behaves in these diverse environments,” notes Aaron Mills, a research scientist in agronomy with AAFC-Charlottetown. “Here in the Maritimes, our growing conditions are more similar to Quebec than Ontario. But, especially with barley, we have a really high propensity for pre-harvest sprouting in our high-moisture environment.”

Breeding priorities

The Ottawa program works on a broad range of spring barley types, including feed, malting and food, 2-row and 6-row, and hulled (covered) and hulless types.

“Around 80 per cent of my breeding program focuses on feed barley; 2-row feed barley is almost 60 per cent of my program and 6-row is about 20 per cent. Then, 18 per cent is focused on malting barley. Although only two per cent is focused on hulless barley, that includes both food and feed types and 2-row and 6-row types,” says Khanal. “We emphasize feed barley because of the high demand from our growers.”

Fewer growers tackle malt barley production because the moist conditions common in the east tend to increase the risk of issues with disease and pre-harvest sprouting. As a result, reliably achieving malt quality can be challenging and usually involves more intensive management than feed barley production. Nevertheless, the breeding program develops some malting and hulless varieties because of the possible niche market opportunities in local craft malting and brewing industries or specialty feed or food businesses.

Improving yield is Khanal’s number one breeding priority because growers are paid by the amount they produce. Agronomic top priorities include improving lodging resistance and early maturity. In terms of disease resistance, Fusarium head blight (FHB) is a major focus. Khanal and his team tap into diverse germplasm from international sources for FHB resistance genes, and screen their breeding materials in the FHB nursery at Ottawa. In addition, the breeding lines are screened for various leaf diseases and stem rust in Western Canada.

Five years, six varieties

Khanal’s breeding program receives funding through the National Barley Cluster – a collaboration between AAFC and the Barley Council of Canada – under the Canadian Agricultural Partnership AgriScience Program. Other funders include the Saskatchewan Barley Development Commission, Alberta Barley Commission, Western Grains Research Foundation, Brewing and Malting Barley Research Institute, Grain Farmers of Ontario, Producteurs de grains du Québec, SeCan, Manitoba Crop Alliance, and Atlantic Grains Council.

Since 2018, the Ottawa breeding program has released six barley varieties, including four 2-row feed varieties: AAC Ling (2018), AAC Bell (2018), AAC Madawaska (2019), and AAC Sorel (2021). Khanal says, “Both AAC Ling and AAC Bell are licensed by SeCan. They are both high-yielding with very good lodging resistance, and AAC Bell also has a high test weight. Both are well adapted to Quebec and the Maritimes. AAC Ling received a gold award for the top barley yield of 2.49 tonnes per acre in the Yield Enhancement Network competition in the Maritimes in 2021.” AAC Ling also has fair malting quality.

“AAC Madawaska is licensed by Eastern Grains Inc. It has a high test weight and yield. It is adapted to Quebec and the Maritimes,” he notes. “AAC Sorel is licensed to SeCan. It has a very high yield, high test weight, high 1,000-kernel weight, very good lodging resistance and moderate susceptibility to FHB. It is suited to production in Quebec and the Maritimes.”

The program has also released one 6-row feed barley, AAC Cranbrook. “It has a high yield and good lodging resistance and is adapted to Ontario. SeCan licensed it in 2021.”

Khanal has a new 6-row hulless variety called OB2705n-11, which is still in the process of registration. “It has a high yield and good lodging resistance, and is adapted to production areas in Eastern Canada.”

Khanal examines speed breeding work at the Ottawa Research and Development Centre greenhouse.

Hulless pros and cons

Hulless barley is not actually hulless – the hull is loosely attached to the seed and is removed during combining. Khanal notes the acres seeded to hulless barley in Eastern Canada are currently very low. “Perhaps if we have more awareness about the benefits of hulless barley, some niche markets will develop and the acres will increase.”

He points to a number of positives about hulless barley. For example, the swine industry is interested in hulless barley’s higher digestible energy and higher protein content. Hulless barley also has a lower risk of contamination by Fusarium toxins because hull removal during harvest eliminates most of those toxins, if present.

“Hulless barley is a more nutritionally packed package compared to hulled barley; it definitely has a higher feed value,” notes Mills. “And hulless barley may have advantages for brewing if it can meet some of the brewing specs.”

In addition, the high levels of beta-glucan in some hulless varieties are important for food uses; beta-glucan is a type of dietary fibre with proven human health benefits. Khanal adds, “I got support for registration of a hulless food barley variety that has a really high beta-glucan level – over 10 per cent – along with a high protein content. I’m still looking for a commercial licence for that one.”

One key issue for growers is that hulless barley is usually lower yielding than covered barley. Khanal sees a few reasons for that. “The main factor is that the hull attached to covered barley makes up about 15 per cent of the grain’s total weight,” he says. So hulled barleys automatically have a weight advantage over hulless barleys.

“Another factor is that we have lots of investment in breeding covered barleys in terms of bringing together genetically diverse materials for making selections and crosses. With hulless barley, we have a much smaller pool of breeding material, so making genetic gains is not easy.”

Mills agrees, “Much more money and work have gone into breeding hulled barley varieties than hulless. As a result, we have more hulled varieties that are more suited to more environments.”

As well, even though hulless barley has a higher nutrient value per unit weight, Khanal notes buyers currently pay the same price for hulless as for covered barley grain.

Hulless seeding rate trial

As part of his breeding program, Khanal travels to different barley-growing areas in Eastern Canada and talks with growers about their research needs.

“I found that in northern Ontario, such as the New Liskeard area, as well as some parts of Quebec, growers are really interested in hulless barley for feeding, especially in the swine industry,” he says. “Based on that, I looked through the literature to find production recommendations for hulless barley. I didn’t find any seeding rates specifically for hulless barley in Eastern Canada.”

Khanal suspected hulless barley would need higher seeding rates than covered barley to achieve its maximum yield potential. “Since the embryo is more exposed in hulless barley, it is more at risk of mechanical damage during harvesting, cleaning and seeding. As a result, it may have lower germination and establishment.”

To fill this information gap, Khanal launched a project on seeding rates for hulless and covered barley in Eastern Canada in collaboration with Mills. The two-year project took place in New Liskeard, Ottawa, Normandin, Que., and Charlottetown in 2018, and all sites except New Liskeard in 2019.

It compared three hulless varieties – AAC Azimuth (6-row), AAC Starbuck (2-row) and CDC Ascent (2-row) – and three covered varieties – AAC Bloomfield (6-row), AAC Ling (2-row), and CH2720-1 (2-row). All the AAC varieties and the advanced line CH2720-1 were developed by the Ottawa breeding program. CDC Ascent is a high beta-glucan food barley adapted to Western Canada, bred by the University of Saskatchewan.

The project team compared six seeding rates: 250, 350, 450, 550, 650, and 750 seeds per square metre. In Eastern Canada, the barley seeding rates used in performance trials and recommendation tests are the same no matter whether covered or hulless varieties are being grown. These rates are: 250 to 350 seeds per square metre in Ontario; 350 to 400 in Quebec; and 350 in Atlantic Canada. In areas such as Alberta and Virginia that have rates specifically for hulless types, the recommendations are at least 400 seeds per square metre.

“In our study, we found that the optimum seeding rate differed between covered and hulless barley,” says Khanal. “For covered barley, the optimum rate was 250 to 350 seeds per square metre. For hulless barley, the optimum rate was 450 to 550 seeds per square metre.”

Mills adds, “We definitely need to increase the seeding rates for hulless barley above what we would normally use for hulled barley. Also, I think our seeding rates are a little low on barley in general on the East Coast; we don’t carry a lot of yield on our tillers, so increasing the seeding rate is a good approach for us.”

Khanal thinks that if growers use a good quality hulless variety and good management practices – including seeding rates around 500 seeds per square metre – then hulless yields will improve.

A century of better barley

“This past year was the hundredth anniversary of the first barley variety released from the Ottawa breeding program in 1922,” notes Khanal.

A century ago, the federal breeding program was using what were then considered innovative methods, such as cross-breeding, systematic selection, and propagation of pure lines. Nowadays, the Ottawa program continues this strong tradition, using the latest breeding technologies to create elite barley varieties adapted to Eastern Canada’s diverse growing conditions and end-user needs.