Features

Research

A valuable research legacy

The oldest long-term agroecosystem experiments in Canada continue to inform research today.

April 21, 2021 By Donna Fleury

An old welcome sign at the corner of Rotation ABC in Lethbridge, Alta. Photo Courtesy of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada archives.

An old welcome sign at the corner of Rotation ABC in Lethbridge, Alta. Photo Courtesy of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada archives.

Agriculture ecosystem research has a long and rich history on the Prairies, continuing today to address new and emerging research issues such as sustainable cropping systems and climate change. An effort is underway to ensure this valuable and unique dataset of long-term experiments remains an accessible resource for informing current and future research questions.

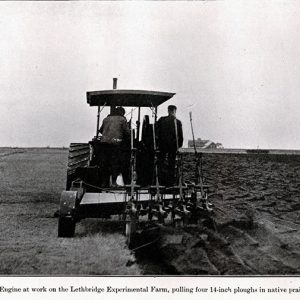

“We have the oldest and longest running agroecosystem experiments in Canada that were started here at the Lethbridge Research and Development Centre in 1910,” says Charles Geddes, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). “Some of these long-term experiments have been ongoing since the native prairie was broken in 1910, and certain data has been collected annually from these plots over the last 110 years. This gives us a very unique and valuable multi-decadal research resource. Today, we continue with 18 different long-term experiments focusing on crop production and agroecosystems. This knowledge is now being used to address emerging issues such as climate change, sustainable cropping systems, carbon sequestration and nutrient cycling.”

One of the first and longest experiments, known as Rotation ABC and located next to the Lethbridge Research Centre, was part of a larger experiment started in 1911 trying to determine what crops would grow best and the most optimum and economic crop sequences in southern Alberta. Three of the several dryland experiments continue today and include A (continuous wheat), B (fallow-wheat) and C (fallow-wheat-wheat). Rotation ABC has continued to be used as a check or benchmark for various other experiments over the years. Rotation U, established in 1911, focused on irrigated crop rotations. Other long-term experiments were initiated in the mid-1950s, some in the 1980s and ’90s, and continue today. Across the Prairies, other long-term AAFC experiments continue in Saskatchewan in Scott, Swift Current and Indian Head.

Geddes adds this long-term history provides a very unique timeline of consistent data collection over a century and a timeline of changes and adoption of new technologies and farming practices. The original plots were managed using horse drawn farm equipment and tillage, and have evolved over the years to no-till systems, chemical pest management and modern cultivars. These long-term datasets show how those plots were managed over time, changes in crop productivity and soils under the various treatments, along with comprehensive weather and climate data. Over time, the research has shown an improvement in crop productivity, mainly due to the adoption of new practices, technologies and varieties introduced over the last century.

Rotation 120 is another long-term experiment started in 1951 that includes various crop rotations and over the years adding diversity not only of crops but also alternative N sources. The experiments included comparisons of inorganic fertilizer with manure applications and other amendments, the addition of N fixing perennial crops and the use of forage or cover crops. This rotation has evolved over time, but the main core rotations have stayed the same. Other experiments focus on long-term soil quality, factors such as erosion and climate and how they affect long term crop productivity and how crops and soils cope with change over time.

“The research questions for various systems have changed over time and having these long-term experiments provides the opportunity for adding new questions and experiments to existing plots,” Geddes says. “In the late-1960s, for example, the Rotation ABC plots were overlaid with different fertilizer treatments, comparing with or without nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer and the impacts on productivity. Questions around soil organic carbon (SOC), productivity and sustainability are just as relevant today as early on. One of the very relevant findings that continues to inform our current research is the impact on SOC once the native prairie was broken,” Geddes explains. “Generally, there was a rapid decline in SOC, with the continuously cropped systems showing less decline than those experiments including fallow in rotation. The continuous and multiple decades of research is even more valuable today as we address big questions around carbon sequestration, climate change, productivity risk, sustainability and long-term economic viability.”

Going forward, Geddes is working closely with a network of more than 20 other AAFC researchers who have been involved with the experiments to bring this valuable long-term dataset together into an easily accessible resource. The goal is to provide an integrated database that can be used as a reference point for the various research experiments, some of which are not well known, and for future experiments. “When we are dealing with long-term experiments from over the past 100 years, we have experiments passed down from generation to generation of various researchers who have worked at AAFC over the years. When passing an experiment on to new researchers it is really important to avoid any loss of important information or data as some of our scientists retire. Therefore, we are trying to develop a single data management platform to house the information for any researchers who have an interest in building on existing long-term data with new research questions.”

Along with the extensive datasets, Geddes notes for soil scientists another long-term valuable resource is an archive of actual soil samples that have been collected from the experiments and stored dating back to 1910. This is a very interesting resource for scientists to take advantage of and has relevance for new work, such as new molecular technologies focused on the soil biome and other new technologies. It can also help inform model development that can further an understanding and quantification of the interaction of management and climate on SOC, crop productivity and sustainability in prairie agroecosystems.

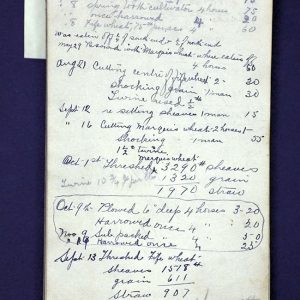

“We are using a phased approach to integrate the decades of information and our long-term goal is to digitize all of the old data and handwritten records as well,” Geddes explains. “ We are starting with yield data and plot metadata for how plots were managed over time and then adding various soil and other factors such as SOC, soil nutrient status, soil quality and climate. As part of this project we are developing a stewardship committee to manage the long-term experiments. It is important to not just continue the experiments just for the sake of continuing them, but rather there has to be some sort of foreseeable value. This committee will assess the various long-term experiments and determine whether they will have utility in the future, or if they don’t maybe it is time to start a new long-term experiment instead to address a more current topic or new research questions.”

“We are looking forward to integrating this unique and valuable long-term agroecosystem resource that AAFC has invested in over the years into a more accessible database system for our researchers. We know this legacy of experiments, datasets and knowledge has already been very useful over the years and continues to help inform current research questions around sustainable cropping systems and climate change. This long-term agroecosystem resource will continue to be valuable for addressing other research questions into the future, some we likely haven’t even thought of yet.”