Features

Agronomy

Diseases

Pests

A new understanding of an old threshold

An updated threshold for lygus bug in canola illustrates the challenges of developing insect economic thresholds.

April 1, 2022 By Jennifer Bogdan

Fifth instar lygus nymph with developed wing pads (left) and adult lygus bug (right).

Photos courtesy of Jennifer Bogdan.

Fifth instar lygus nymph with developed wing pads (left) and adult lygus bug (right).

Photos courtesy of Jennifer Bogdan. One of the great things about entomology research is that as more is learned about individual insects, management strategies toward them can be better adjusted. Such is the case for lygus bug in canola. Héctor Cárcamo, research scientist from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Lethbridge, has been studying lygus bug for more than 20 years, and during this time has found that lygus feeding on canola is not always damaging, but at times can actually stimulate a yield increase in the crop. Because of this unique insect-plant dynamic, Cárcamo sought to revisit the economic threshold of lygus bug in canola, with the hunch that unnecessary insecticide applications were being made in an effort to control an insect that wasn’t causing as much damage to canola as initially thought. He also recognized that the hybrid cultivars being used today are higher yielding, earlier maturing, and more shatter resistant, potentially tolerating more insect feeding compared to the cultivars used when the lygus threshold was developed a few decades ago.

Cárcamo has been reworking the economic threshold for lygus bug in canola since 2012, first with cage studies (2012-2015), followed more recently with on-farm field-scale validation studies (2016-2020). To do so, the economic injury level (EIL) needed to be calculated. The EIL refers to the number of insects that begin to cause economic damage, and incorporates costs such as the market value of the crop and the cost of controlling the insect (insecticide plus application). The economic threshold (ET) is the level of damage or pest density when control (ex. spraying) should take place, as the damage caused by the insect past this point will cost more than the control of the insect. Essentially, the ET is when control action should occur, which is why it is often referred to as the action threshold. For lygus bug in canola, the EIL and the ET are the same number because it is assumed that insecticide will be applied immediately to control the insect and damage to the crop will stop.

The challenge: Lygus bugs aren’t always a bad thing

Though determining a new EIL may sound like simply plugging numbers into a standard mathematical equation, Cárcamo emphasizes that with a complex insect like lygus bug, there was nothing simple about the threshold calculation.

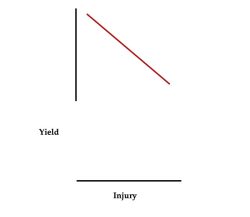

“In order to determine the yield loss from an insect (one component of the EIL equation), you rely on a linear regression to relate the crop yield to the insect. This type of regression produces a straight, downward-sloping line. But the challenge with lygus in canola is that under low lygus numbers, they can actually benefit the crop in the form of increased yield, then after a certain density level, they have no effect on the crop, and then at higher density levels, they can start to injure the crop. Also, if you have higher moisture levels from rainfall or under irrigation, the crop can compensate for additional lygus feeding. So there are challenges with using linear regression because in reality, the graph would be more curved, rather than a straight line,” he explains (Figure 1).

The original economic threshold for lygus bug in canola (developed in 1998) was calculated to be 1.5 lygus per sweep at the early pod stage. This threshold value is often seen translated into a chart form, with the lygus threshold numbers being adjusted depending on crop price and cost of spraying. Because these charts allow the user to look up the lygus threshold based on an ever-changing crop value, they’ve maintained their popularity with those deciding when to spray. Based on the charts, as crop prices increase, the ET decreases. So when canola hit record-high prices of more than $20 per bushel, wouldn’t a reduced ET be justified in order to protect the crop value? Not necessarily, according to Cárcamo.

“We need to move away from using the lygus threshold values that are displayed in the chart form. In these charts, as the crop price increases, the threshold for lygus decreases to levels that are no longer realistic, such as 0.5 lygus per sweep or less. The issue here is that the chart assumes the relationship between lygus and yield is linear, but this is not the case since plants can overcompensate at low lygus pressure and have a positive effect on yield, not always a negative effect like the chart alludes to. Instead, we should be focusing on what the crop can tolerate rather than on the price the crop is worth,” he says.

The new ET: three lygus per sweep at early pod

Based on Cárcamo’s combined cage study and on-farm field-scale research, the new threshold for lygus bug in canola appears to be three lygus per sweep at the early pod stage. Lygus bug counts should include third instars (when developing wing buds are first visible), fourth instars, fifth instars, and adults.

Cárcamo elaborates, “Even at this new threshold, results from spraying are extremely variable. One year you can get significant effects and the next year you don’t have any yield differences between the sprayed and unsprayed. We won’t have the final word until the data is published, but for now, it looks like the threshold is at least three lygus per sweep. In some cases, notably in humid regions, that threshold may be even higher at five lygus per sweep. If you’ve planted early, where we typically don’t see high lygus numbers, and looked after your fertilizer, crop density, and everything else to establish a healthy crop, there’s a good chance you won’t have to spray for lygus on a typical year.”

The proof is in the field-testing

Josh Fankhauser farms 7,000 acres near Claresholm, Alta., and has been conducting on-farm insect trials with Cárcamo for the past 10 years. Through the numerous replicated trials and countless hours scouting on his own farm, Fankhauser’s lygus bug threshold results and experience align with Cárcamo’s findings.

Figure 1: Linear regression assumes as crop injury from insect feeding

increases, crop yield decreases.

“As a general rule on our farm, we’ve used double the traditional threshold for lygus. At 1.5 times the threshold (1.5 to two lygus per sweep), we start increasing our frequency of scouting. But we’ve often found that the lygus pressure plateaus and hovers around that 1.5 times threshold level. The beneficial insects seem to catch up and the plants can compensate for lygus feeding, especially in canola under good moisture such as on irrigation,” he says.

Fankhauser says looking beyond the strict ET number and considering the greater picture of what is happening with insect populations in a field have allowed him to push his threshold tolerance. He explains: “You have to remember that the threshold value is an economic threshold, not a biological threshold. If you’re a strict numbers person, maybe you would end up spraying all the time. But some lygus feeding isn’t necessarily bad. You have to consider the beneficials as well – and they don’t bounce back as quickly as the pest. If you’ve ever looked at a field when it’s safe to re-enter after spraying an insecticide, there’s nothing buzzing, there’s no life. It’s eerie.”

When it comes to beneficial insects, Cárcamo whole-heartedly agrees. “Natural enemies and beneficial insects are another reason for not being so sticky on the economic threshold number – you need to leave some wiggle room for these insects. We know there’s a value to having them in our crop, but unfortunately we don’t know how much,” he says.

On Fankhauser’s farm, the key to lygus management is diligent scouting: “Keep walking those fields and constantly watching the daily changes in lygus numbers. Pay more attention to where the lygus are coming from, such as field edges where lygus are moving in from the ditches. We also always have insecticide in the shed because when you’re pushing the threshold, you need to make sure you have product. We have our own sprayer but if you have to hire a custom applicator, you need to take your wait time into consideration and may not be able to push the threshold as much.”

For Fankhauser, the question of “to spray or not to spray” for lygus comes down to really understanding his own numbers, from both an insect as well as an economic point of view. He says, “Usually, if we just wait for the lygus counts to level off, we find that they do and we don’t have to spray. Sometimes we can just spray the outside two rounds and have success. In the past, we have regretted blanket spraying, or not doing a good enough job of scouting. But we’ve rarely regretted not spraying – it’s easy to forget about the money you saved not spraying all of those years, even if you didn’t spray one year and maybe should have.”