Features

Agronomy

Plant Breeding

Biofuels breakthrough

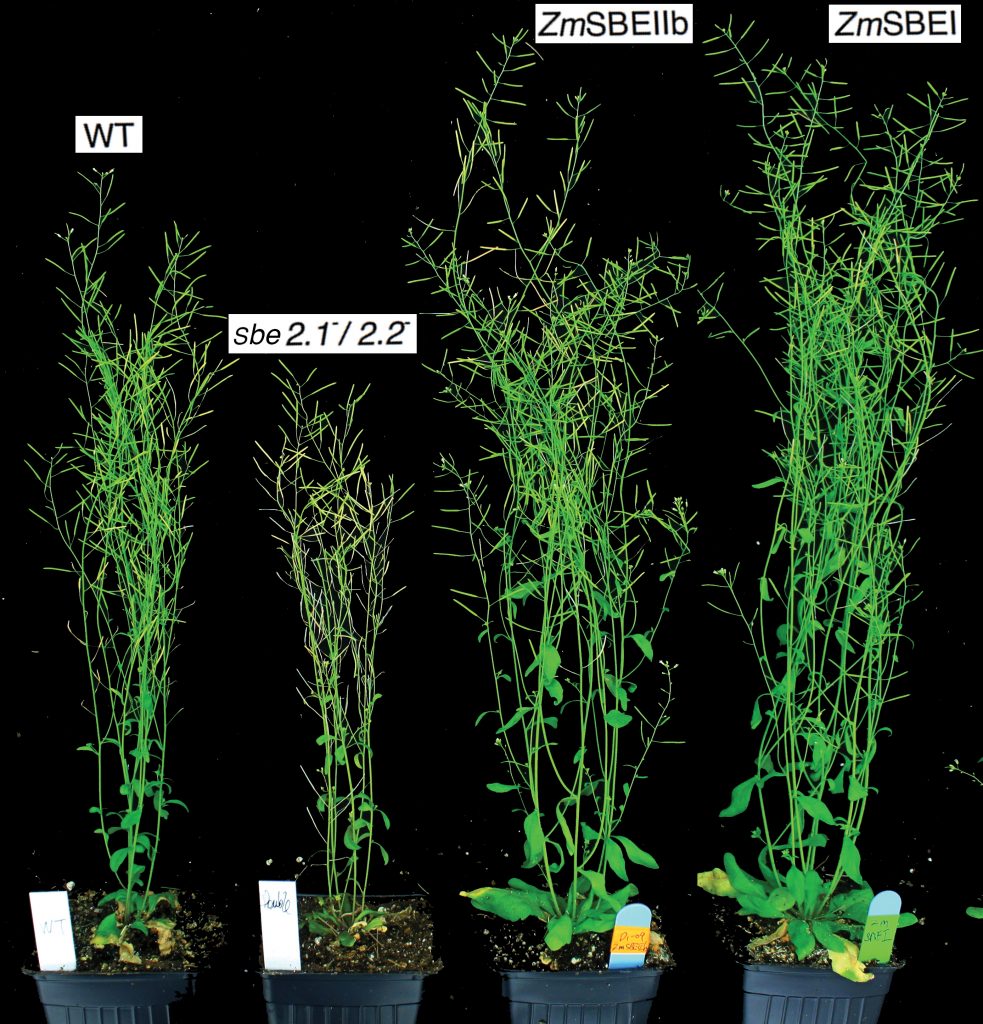

Fushan Liu never expected the sight that greeted him last year in his lab at the University of Guelph: arabidopsis plants grown two and a half times their normal size.

As a postdoc at the University of Guelph’s College of Biological Science, Liu had been working on a project transforming starch branching enzymes (SBEs) from maize into arabidopsis plants. For weeks, he’d been analyzing the interesting effects of the maize SBEs on the arabidopsis plants’ starch pathways. Then one day he realized the plants he’d been working on had grown much larger than the control plants. Not only that, but there were also far more seedpods, and their leaf and root systems were bigger, too.

“That was the beginning – I saw a really big arabidopsis plant and thought, let’s take a picture. Something has happened biologically,” Liu says.

He showed the photo to his supervisors, Guelph professors Michael Emes and Ian Tetlow.

“We’d found some interesting effects on the starch, and had done all sorts of measurements,” Emes echoes. “And then one day we stood back and looked at the plants, and we finally saw the wood for the trees. We saw these plants were really different.”

A healthy plant from a typical arabidopsis line normally bears about 11,000 seeds; the new plants bore 50,000 seeds per plant – a more than 400-per-cent increase in seed production.

“The plants were bigger, the leaves were bigger, there were more stems, there was more flowering and more seed,” Emes says. “It’s not just that there were a lot more seeds, there was a lot more of everything.

“It was one of those serendipitous events in science. If you’d asked me to produce a plant with more seeds I would have said you couldn’t get there from here,” he adds.

Liu’s focus had been on trying to analyze how the SBEs’ functions changed in arabidopsis leaves, but after this discovery his focus changed to studying the impact on seed yield and biomass, comparing transformed plants with wild-type arabidopsis plants. Importantly, the quality of the oil remained the same as for the non-transgenic plants.

The team published their findings this spring in the Arabidopsis is not a starch crop, but an oilseed genetically similar to canola, so the obvious application of the finding is in breeding higher-yielding oilseed crops for biofuels. Emes and Tetlow have already begun preliminary work with canola, but also foresee potential applications in camelina, soybeans and other crops.

While the dramatic increase in seed production might not occur as easily in canola as in arabidopsis, Liu says even a tenth of the effect would still mean an increase of 40 per cent – a substantial impact on yield.

“This is orders of magnitude different than conventional breeding,” Emes says.

But what, exactly, is going on in the plants?

The good times are here

Emes has a theory that the starch metabolism in the transformants has improved the plants’ ability to grow and reproduce.

The team is working on two lines using two starch genes from maize. In one of the new lines, there is a massive increase of starch in the leaves, which the plant breaks down overnight. In the other line, there is a bigger impact on yield; there is still an increase in starch in the leaves, but it doesn’t all break down at night, leaving a carbohydrate reserve.

“We know that carbohydrates, during seed development, come from the leaf through the vascular system and into the reproductive system. These are important to flower development and what’s called embryo abortion – the plant makes a kind of ‘decision’ on whether or not to produce seeds,” Emes explains. “Flower and seed production is limited by the supply of carbohydrates. So these plants are now saying, ‘The good times are here, let’s go for it.’ ”

Emes suspects that the wild type arabidopsis plant has an endogenous mechanism that constrains growth because it’s genetically evolved to always keep something in reserve. But in the transgenic plants, the brakes have been taken off.

If the scientists can crack the code on the maize SBEs’ effect on oilseeds, Emes sees potential applications for feedstock and oil for human consumption, as well as biofuels. He is currently seeking public and private funding to continue the project in canola.

Liu, now a regulatory scientist for the J.R. Simplot Company, says much more work is required to improve seed quality as well as yield in future breeding projects. “If you want to improve quality, if you want to improve omega-3 fatty acid or other special fatty acid content, for now I don’t have any insight on how you can improve those things, from this study,” he says. “At least, from the analysis of the arabidopsis you don’t see a change in these properties – you just get higher yields.”

But Liu is optimistic about the future applications of his work. “Genes are so powerful,” he says. “One small change could be a potential opportunity for dramatically improving crops.”

November 8, 2016 By by Julienne Isaacs

Wild type (WT) arabidopsis plants

Wild type (WT) arabidopsis plants