Features

Insect Pests

Know your enemy

Broflanilide is set to provide improved wireworm control, but a greater understanding of the pest is still necessary.

June 1, 2021 By Alex Barnard

Adult and larval stages of the main pest wireworm species on the Prairies. From left to right: Hypnoidus bicolor (no common name), Selatosomus aeripennis destructor (Prairie grain wireworm), and Aeolus mellillus (flat wireworm). Photo courtesy of Haley Catton.

Adult and larval stages of the main pest wireworm species on the Prairies. From left to right: Hypnoidus bicolor (no common name), Selatosomus aeripennis destructor (Prairie grain wireworm), and Aeolus mellillus (flat wireworm). Photo courtesy of Haley Catton. Wireworms are a particularly pesky pest on the Prairies. While there are chemical control options that prevent wireworms from feeding on a crop or paralyze them, there hasn’t been a pesticide capable of killing them since the Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) cancelled registration of lindane in late 2004.

With the PMRA’s registration in November 2020 of broflanilide, the first Group 30 insecticide on the market, that’s set to change.

“What’s been missing for a number of years in crop protection is a registered pesticide that will kill wireworms,” says Haley Catton, research scientist and entomologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lethbridge, Alta. “In recent years, the ones that have been registered in cereals, pulses and even potatoes have been effective at protecting crops through paralyzing the wireworms or repelling them – pushing them away in the soil. But they haven’t been reducing wireworm populations enough to provide multi-year control.

“So that means those same wireworms, because they live for multiple years, are there in your soil just waiting for next year’s crop. That would mean a producer would require consistent applications every year, even while the wireworm populations build up and build up because there’s nothing killing them.”

Applying pesticide for use in this manner isn’t uncommon, but it is costly, especially if the return on that investment is small. But Catton notes that, through conversations with colleagues who have yet unpublished research on broflanilide’s effects, it has huge potential for within season and multi-year wireworm control.

“There’s only one published study on broflanilide and wireworms so far, because it’s a pretty new chemical. That study described field trials in B.C. and showed that [broflanilide] protected wheat stand similarly to other chemicals, but also reduced wireworm populations, which was unique among the registered chemicals tested,” she explains. The current market formulation of the other recent new formulation registered for wireworm, a diamide, was not included in that study. “So, if a chemical can reduce your wireworm populations, that means maybe you don’t need to apply it next year as well – you’re knocking back the number of wireworms.”

While it’s early days yet, broflanilide shows promise as a replacement for lindane.

“The published study showed that [broflanilide] was killing 70 per cent of the wireworms in the treated plots. That was a seed treatment on wheat, but 70 per cent is a really nice knock-back number, and that’s very similar to what we would see with lindane back when it was still registered,” Catton says.

“What’s really interesting about broflanilide too, is that – at least in cereals – you could apply it as a seed treatment and it has enough residual to kill the new hatchlings that would hatch from eggs several months after seeding. By seed-treating in the spring, you’ve killed last year’s wireworms, but you’re also killing this year’s because new hatchlings are going to be killed by the chemical, too.”

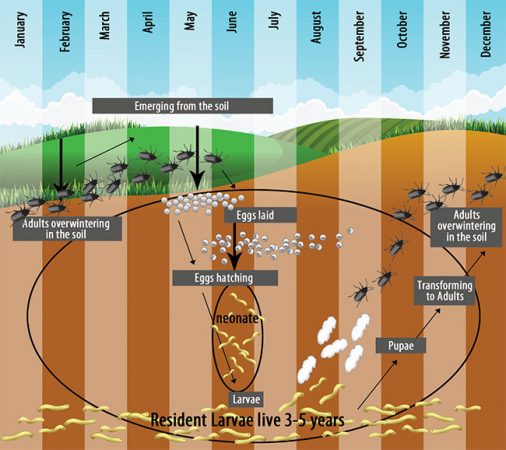

The life cycle of a wireworm. Image by Top Crop Manager.

Big picture problems

A serious problem in wireworm control is the lack of research and information on the pest.

“There are multiple species [of wireworm] in on the Prairies: hundreds of non-pest species, and four or five main pest species,” Catton says. “[However] there are no surveys done at all for wireworms. The damage is really hard to pin on [them].

“We don’t really have a good way of monitoring wireworms reliably and we also don’t have economic thresholds. Keep in mind we’re talking about multiple different species with different behaviours, so it’s a very complicated problem to try to solve,” she adds.

“The only really reliable control we have for crop protection are chemicals at the moment, but we’re hoping as research goes forward to have new tools available.”

Catton notes that there is a great deal of research and work being done on wireworms in Canada at the moment. Pending funding, she plans to work on a project on wireworm thresholds on the Prairies this spring. She was also part of a team analyzing the pheromones produced by females of certain species of the beetle stage of wireworms, which attract male beetles for mating.

“One thing people have done for European wireworm species is synthesize those pheromones so we can put them in traps and have a bunch of beetles come to those traps – so you can easily monitor what species are around and how many,” Catton explains. “There’s been major advancements in that on the Prairies; I’m part of a team where we isolated new pheromones for two new species – those tools weren’t available before.”

Catton and her colleagues have created a new wireworm field guide for the Prairies, which will be available later this year. She notes that the complexity of wireworms as a pest means more research is necessary. While some fields may be devastated by wireworms, other growers might not have ever experienced any damage and believe the threat wireworms pose is overblown.

“In terms of the research, it needs to keep going because [wireworm is] a patchy pest that’s made up of multiple species,” she says. “That makes it very different from a pest like wheat midge or wheat stem sawfly or something that’s just one species. We’re talking about multiple species with different life cycles, different behaviours, different feeding behaviours; some of them need to mate, some of them don’t.”

“There’s no black and white with wireworms, unfortunately,” Catton says. “The whole thing is complex.”

Wireworm control can be difficult, but the registration of broflanilide is promising for Canadian growers. Photo courtesy of Wim Van Herk, AAFC.

Like a surgeon

On the topic of pesticides more broadly, Catton hopes to shift perceptions of when to use them.

“One way to think about chemicals is insurance,” she says. “You could say, ‘I’m not sure what’s going to happen, so I will invest in this treatment to prevent it from happening.’ But there are hidden costs with that: not only the cost of the chemical in the application, but also any of the non-target effects to beneficial insects that might be controlling some other pests you have in your field.”

“An insurance salesperson might say, ‘Better safe than sorry,’ but as entomologists we’re trying to shift that perception: yes, there is something to lose by applying when you don’t need to.”

Catton likens entomological research on pest insects to laparoscopic surgery. “I think a more historic mentality would have been, ‘Let’s sterilize this field, let’s kill everything in that field.’ But we know from research how important those other insects in the agro-ecosystem are. They eat weed seeds, they eat pests – they eat and they poop, so they’re cycling nutrients,” she says.

“We want to be surgical – how can we get in there and reduce the populations of the ones we don’t want, and leave everything else we do want. That’s the future for insect pest control.”