Features

Agronomy

Irrigation

Managing irrigation to optimize crop production

Many irrigation farmers tend to under-irrigate their crops, which limits yield potential. To do a good job of managing irrigation, farmers need to know the amount of water their irrigation systems are capable of applying, the water holding capacity of their soils, the amount of water each crop uses throughout the growing season and how to check soil moisture levels in their fields.

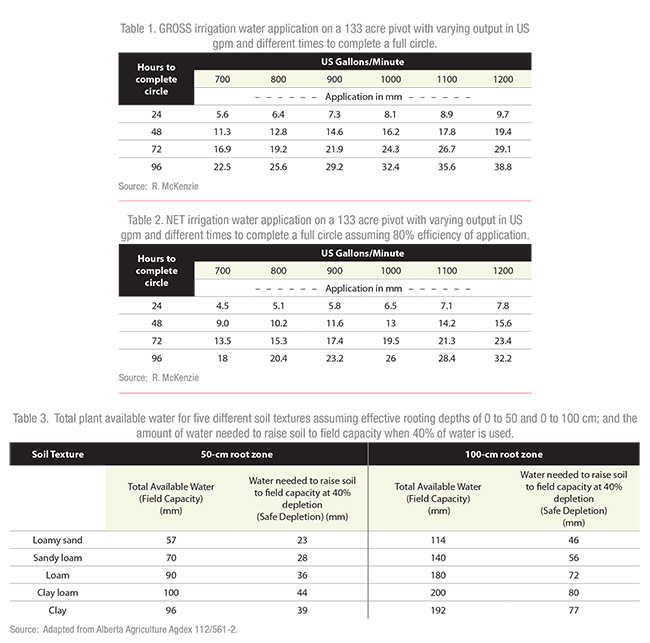

The majority of irrigated fields in Western Canada are irrigated with pivot systems. Table 1 shows the GROSS water application of a low pressure quarter section pivot, irrigating 133 acres, with various water outputs in US gallons/minute (US gpm) at different application times. The GROSS water application rates are in millimetres (mm).

Table 2 shows the NET water application, assuming an 80 per cent efficiency rate. NET water application is the amount of water that actually enters the soil. Typically, low pressure pivot systems with drop tubes and pressure regulated spray nozzles have an 80 to 85 per cent efficiency of water application, depending on environmental factors including air temperature and wind speed. High-pressure pivot systems with impact nozzles typically have water application efficiency in the range of 75 per cent. Side roll-wheel move systems have water application efficiency in the range of 70 per cent.

As an example of water application, a low pressure pivot with a 900 US gpm output that makes a full circle in 48 hours (two days) has a GROSS water application rate of 14.6 mm (from Table 1) but the NET application rate at 80 per cent efficiency is only 11.6 mm (from Table 2). A common mistake made by irrigators is not estimating NET water application. If a pivot can only apply 6 mm of water per day, and crops use 8 mm of water per day, the irrigation system will not be able to keep up with water use during peak periods.

|

Know your soil’s water holding capacity

Soil should be viewed similar to the varying sizes of fuel tanks on vehicles. Sandy soils have lower water holding capacity or a small fuel tank, while a clay loam soil has relatively larger water holding capacity or large fuel tank.

Two terms to know and understand are “field capacity” and “safe depletion point.” Field capacity is the total amount of water a soil will hold, which is also called “total available” soil water. Table 3 provides the approximate amounts of total available soil water for five major soil texture classes and the amount of “readily available” soil water in the 0 to 50 cm and 0 to 100 cm depths. As crops are taking up water, the amount of available water is drawn down. As this occurs, remaining soil water is held more strongly within soil pores and plants must gradually work harder to take up the remaining soil water. Readily available water is the amount of water crops can easily take up, but after this water is used, crops begin to suffer, wilting during the day, and yield losses will occur.

Safe depletion point is the amount of water that can be safely used by crops without crop yield loss, but when this point is reached it is time to irrigate soil back to field capacity. Ideally for most irrigated crops, you should only use about 40 to 50 per cent of the total available water (safe depletion point), and then it is time to irrigate soil back to field capacity.

Annual crops such as wheat and canola typically will root down to about 100 cm (40 inches) and can effectively take up moisture to 100 cm by the time of heading for cereals and flowering for canola. Under ideal conditions at heading or flowering, most annual crops will take up 70 per cent of water requirements in the 0 to 50 cm depth and the remaining 30 per cent of water requirements in the 50 to 100 cm depth.

Irrigators must be very aware of the amount of crop water use of annual and perennial crops throughout the growing season. Moisture use starts off at relatively low rates in early May, but as vegetative growth rapidly increases, so does daily water use. Depending on the crop, peak water use can range from six and nine mm/day of water, depending on evapotranspiration conditions including maximum air temperature and wind speed. Southern Alberta farmers have access to the Irrigation Management Climatic Information Network (IMCIN) weather stations which provide daily crop water use information at sites across southern Alberta at: http://agriculture.alberta.ca/acis/alberta-weather-data-viewer.jsp?stations=imcin. This is very useful for knowing how much water crops are using and to help to predict irrigation requirements.

As crops are growing, irrigators must regularly monitor and determine soil moisture in fields to ensure moisture levels don’t decline below the safe depletion point. There are various ways to monitor soil moisture – a simple and easy way is to use the “feel method.” A hand auger is used to auger down to 100 cm, all the while assessing the soil moisture level at incremental depths. Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development’s Irrigation Manual has a very good table that provides information on the feel of soil at different moisture levels for different textured soils. A good place to start is to check soil moisture in fields the day after irrigating so you know how your soils feel at field capacity. Then get to know how soils feel at 75 and 50 per cent of field capacity. This takes a bit of time and practice but can actually be quite effective to easily check soil moisture on a weekly basis.

Alberta Agriculture’s Irrigation Management Field Book can be used to record and plot soil moisture for each field. It is excellent for recording soil moisture and predicting when to irrigate. Further, Alberta Agriculture has a free computer program model called Alberta Irrigation Management Model (AIMM) which is fairly advanced but a very useful decision-making tool.

June 11, 2014 By Ross H. McKenzie PhD P. Ag.

This demonstration at the Outlook Irrigation Crop Diversification Corp. showed the impact of deficient irrigation on dry beans. Many irrigation farmers tend to under-irrigate their crops

This demonstration at the Outlook Irrigation Crop Diversification Corp. showed the impact of deficient irrigation on dry beans. Many irrigation farmers tend to under-irrigate their crops